Texas Drinking Water — A Lesson for the United States

Texas is the largest state in the continental United States, and home to Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio, three of the top ten most populous cities in the nation. The Lone Star State has pioneered many famous firsts and larger than life landmarks, and seems to do things in its own way. In 1870, Texas built the Waco Bridge, the first suspension bridge in the United States that is still in use today as a pedestrian crossing, and the dome of the capitol building in Austin stands seven feet higher than that of the nation’s Capitol in Washington, D.C. The world’s longest fishing pier is in Port Lavaca, the world’s first rodeo was held in Pecos on July 4, 1883, and the Tyler Municipal Rose Garden is the world’s largest rose garden, with over 38,000 rose bushes representing 500 varieties of roses set in a 22-acre garden. Texas has a total of 6,300 square miles of inland lakes and streams, second only to Alaska, and more land is farmed in Texas than in any other state in the nation, including California.

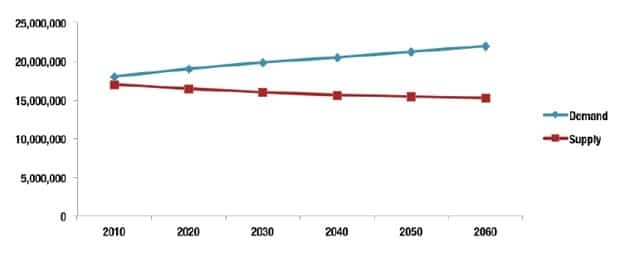

It’s no wonder that Texas is also a national leader in water management. With its massive population, vast farming acres, and generally arid climate, the state has taken proactive measures to ensure that it has adequate water supply for its myriad needs. In 1997, Texas developed its first statewide water plan and has faithfully updated it every five years since then. The statewide plan combines information from 16 regional plans, each with its own 50-year projected water demands as well as strategies for new water supply. Since the population in Texas is expected to increase over 80% by the year 2060, growing from 25.4 million to 46.3 million people, the most recent statewide water plan (completed in 2012) predicts a gap between supply and demand of over eight million acre-feet by 2060, which would require an astronomical $53 billion investment in new water supply strategies. And that $53 billion represents less than a quarter of the total need of $231 billion for water supplies, water treatment and distribution, wastewater treatment and collection, and flood control required for the state of Texas in the next 50 years. As a result of this dismal forecast, Texas voters approved a new $2 billion revolving loan fund in an effort to avoid the insurmountable deficit. The fund provides monetary support for projects in the state water plan, and requires that at least 20% of the funds be used for conservation and reuse strategies and 10% be used for rural areas.

Photo: City of Wichita Falls

Recommendations to increase water supply include reservoirs and wells, conservation, drought management, and desalination. Another strong recommendation is reuse, in which Texas is already a trail-blazing leader. In fact, Texas is the only state in the nation to have implemented direct potable reuse (DPR) in not one, but two cities – Big Spring and Wichita Falls. The Colorado River Municipal Water District (CRMWD), serving the communities of Big Spring, Snyder, and Midland, Texas, spent over ten years researching and testing before determining that their best option was DPR, and in May of 2013, the nation’s first DPR plant, which is capable of treating up to two million gallons of wastewater effluent per day to drinking water standards, was officially opened. Wichita Falls constructed a 13-mile pipeline that connects the city’s wastewater treatment plant to its water treatment plant. Treated wastewater is then piped directly to the water treatment plant for further treatment, with no environmental buffer. However, both plants do mix their wastewater effluent with raw water before treating it for drinking water. As for the “yuck factor” associated with DPR? It was really never an issue. The dire drought conditions and critical need for drinking water made Texans very receptive to DPR. After a few public meetings, press releases, TV and radio spots, and an educational video, local residents were overwhelmingly on board with the idea.

And others have taken notice. California’s Orange County Water District Groundwater Replenishment System (GWRS) is a cutting-edge indirect potable reuse (IPR) system that could be turned into a DPR system if necessary. The GWRS system takes wastewater effluent that would have discharged into the Pacific Ocean and instead purifies it to actually exceed both state and federal drinking water standards. This highly treated water is then discharged into percolation basins in Anaheim, where sand and gravel naturally filter the water prior to returning it to the drinking water system. In addition, the WateReuse Research Foundation (WRRF) and WateReuse California worked together to raise $4 million from 30 different water and wastewater agencies to support research for DPR. And Colorado, whose population has skyrocketed in recent years and is expected to double from its current five million to ten million by 2050, approved the state’s first ever water action plan in November of 2015.

And this is just the beginning. With population increasing exponentially and supply steadily decreasing due to climate change and drought, local and regional communities as well as states and the federal government will have to continually seek innovative, efficient ways to meet the ever-increasing demand. With its comprehensive water action plan, DPR implementation and education, and proactive funding of water projects, Texas has carved an innovative path that is providing much-needed guidance and hope to a thirsty nation.