This month marks the ten year anniversary of Hawaii’s Ka Loko Dam failure on the island of Kauai. On March 14, 2006, after 40 days of heavy rainfall, the rising water finally overtopped the dam near the original spillway — which had been filled in by the owner. At the time, the State of Hawaii lacked resources and legal authority to properly ensure that the owner fully addressed safety concerns. The break sent almost 400 million gallons of water downstream four miles until it finally reached the ocean, and the water reached about 20 feet in height, destroying whatever was in its path, including trees, homes, and vehicles. The disaster, which was entirely preventable, killed seven people, including a pregnant woman and child, and caused millions of dollars of property damage as well as significant environmental damage. As a direct result of the disaster, Hawaii increased funding to its dam safety program, allowing for improved regulation of local dams.

Historic U.S. Dam Failures and Legislation

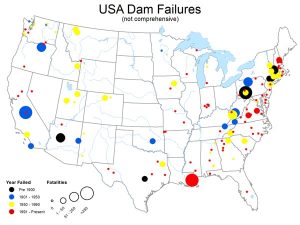

Unfortunately, the Ka Loko Dam failure in Hawaii was not an isolated incident. Dam failures in the United States have caused catastrophic damage and loss of life for well over a century:

May 16, 1874 – Williamsburg, Massachusetts

At 7:20 a.m., the 43-foot-high Mill River Dam above Williamsburg, Massachusetts failed, killing 138 people, including 43 children under the age of ten. At the time, this failure was the worst in U.S. history.

May 31, 1889 – Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Over 2,200 people — more than 20% of the residents of Johnstown — perished in the flood caused by the failure of South Fork Dam, nine miles upstream. To this day, the South Fork Dam disaster is the worst in U.S. history. National Dam Safety Day is celebrated each May 31 in remembrance of the catastrophe.

Around the turn of the century, many more dam failures occurred, resulting in the passing of some early state dam safety legislation.

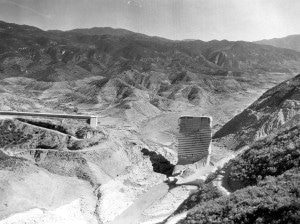

March 12,1928 – San Francisquito Canyon, California

The failure of St. Francis Dam, which killed over 450 people and caused over $13 million in damage, the equivalent of about $180 million by today’s standards, was a landmark event in the history of state dam safety legislation, spurring legislation not only in California, but in neighboring states as well. It was also the worst civil engineering disaster of the 20th century, serving as the catalyst for the engineering licensure requirement in California.

In response to the St. Francis Dam disaster, the California legislature created an updated dam safety program and eliminated the municipal exemption. In addition, the State was given full authority to supervise the maintenance and operation of all non-federal dams. However, even in the wake of such a horrific disaster, most other states had severely limited dam safety laws — that is, until a series of dam failures and incidents occurred in the 1970s:

February 26, 1972 – Buffalo Creek Valley, West Virginia

The failure of a coal-waste impoundment at the valley’s head took 125 lives, and caused more than $400 million in damages, including destruction of over 500 homes.

June 9, 1972 – Rapid City, South Dakota

The Canyon Lake Dam failure took an undetermined number of lives (estimates range from 33 to 237). Damages, including destruction of 1,335 homes, totaled more than $60 million.

June 5, 1976 – Teton, Idaho

Eleven people perished when Teton Dam failed. The failure caused an unprecedented amount of property damage totaling over $1 billion.

July 19-20, 1977 – Laurel Run, Pennsylvania

Laurel Run Dam failed, killing over 40 people and causing $5.3 million in damages.

November 6, 1977 – Toccoa Falls, Georgia

Kelly Barnes Dam failed, killing 39 students and college staff and causing about $2.5 million in damages.

In response to these tragedies, President Jimmy Carter implemented the “Phase I Inspection Program” that directed the US Army Corps of Engineers to inspect the nation’s non-federal high-hazard dams. The findings of the inspection program, which lasted from 1978-1981, were responsible for the establishment of dam safety programs in most states, and, ultimately, the creation of the National Dam Safety Program, which today supports dam safety programs in 49 states. Alabama is the only state in the nation that has yet to pass dam safety legislation, although Alabama State Representative Mary Sue McClurkin introduced a bill on March 18, 2014 which, if passed, would establish a state dam safety program.

Emergency Action Plans

One of the key components of a successful dam safety program for high hazard and significant hazard dams is a comprehensive, up-to-date Emergency Action Plan (EAP). Hazard level does not reflect the condition or age of the dam; rather, it indicates the potential for loss in the event of dam failure. According to FEMA, the classifications are as follows:

High hazard: Facilities where failure will probably cause loss of human life. Such facilities are generally located in populated areas or where dwellings are found in the flood plain and failure can reasonably be expected to cause loss of life; serious damage to homes, industrial and commercial buildings; and damage to important utilities, highways, or railroads.

Significant hazard: Facilities where failure would likely not result in loss of human life, but can cause economic loss, environmental damage, or disruption of lifeline facilities. Such facilities are generally located in predominantly rural areas, but could be in populated areas with significant infrastructure and where failure could damage isolated homes, main highways, and minor railroads or disrupt the use of service of public utilities.

Low hazard: Facilities where failure would result in no probable loss of human life and low economic and/or environmental losses. Such facilities are usually located in rural or agricultural areas where losses are limited principally to the owner’s property or where failure would cause only slight damage to farm buildings, forest and agricultural land, and minor roads.

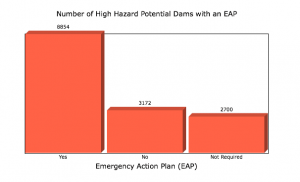

Unfortunately, about 22% of high hazard dams and 40% of significant hazard dams nationwide still do not have EAPs, meaning that thousands of dams across the United States lack EAPs required by law. And dams are still failing. According to the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, 173 dams across the United States have experienced failures since 2005.

The lack of an EAP could be problematic in the event of dam failure, said Mark Ogden, project manager for the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, who also noted that while such worst-case scenarios are rare, they have happened. “An exercised, well-prepared emergency action plan is a valuable tool to help save lives,” Ogden said.

Ogden also noted that even when dams have an EAP, downstream residents often do not know where to find it. “There have been a lot of efforts in recent years to try to make the public aware of dams and the potential dangers, and to know if they live in an area downstream of a dam, the failure inundation zone, who to talk to – whether it’s the dam owner or more likely the local emergency management officials – to find out if there is an EAP for that dam and what they would need to do,” Ogden said.

Legislation

The good news is that most states have responded to the need for dam safety regulations and require EAPs for high hazard and significant hazard dams. The most recent legislation came in February of this year, when the State of Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) adopted new regulations concerning the preparation and update of EAPs for Class C and Class B dams. In 2013, fewer than 60% of regulated high hazard dams in Connecticut had an EAP, a statistic the State is hoping to drastically improve. The new EAP regulations include criteria for inundation mapping, dam monitoring procedures, formal warning notification and communication procedures, emergency termination protocols, and EAP review and revisions.

Currently, the only states without EAP requirements are Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, North Carolina, Vermont, Wyoming, and — ironically enough — California. Since Alabama still has no formal dam safety program, they also do not require EAPs.

ASDSO continues to work alongside the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC), and other stakeholders to promote dam safety and to encourage legislation to protect the public and the environment from disasters such as the Ka Loko Dam failure in Kauai, Hawaii.

“The tenth anniversary of the dam’s failure reminds us of the potential dangers posed by dams and the critical importance of both responsible dam ownership and strong dam safety programs,” said Lori Spragens, executive director of the Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO). “Most dam failures are preventable disasters. Dam owners must keep their dams in the state of repair required by prudence, due regard for life and property, and the application of sound engineering principles. The quality of dam maintenance, emergency planning, and enforcement programs directly affects the safety of communities, as sadly demonstrated on Kauai. With more than 87,000 dams of regulatory size in the U.S., we all have a stake in dam safety.”