The Johnstown Flood of 1889

It had been raining heavily for several days in late May of 1889. People living below in the narrow Conemaugh Valley were eager for the spring rains to end. Just a month earlier, deep snow had lined the steep ravines of the Allegheny Mountains range and the ground was sodden with the heavy spring runoff. Floodwaters at the South Fork Dam high above the City of Johnstown, Pennsylvania were causing the lake level to rise, threatening to overtop the large earth embankment dam.

As the spring rains continued, life was about to change for the working-class city of 30,000 and other communities beneath the South Fork Dam.

As the spring rains continued, life was about to change for the working-class city of 30,000 and other communities beneath the South Fork Dam.

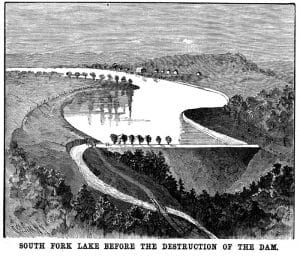

Originally constructed in 1852, the South Fork Dam provided a source of water for a division of the Pennsylvania Canal. After a minor breach in 1862, the dam was hastily rebuilt creating Lake Conemaugh. By 1881, the dam was owned and maintained by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, who created a recreational area by the large lake, enjoyed by their elite clientele from nearby Pittsburgh.

For the pleasure of their private members, club owners soon began modifications to the dam. Fish screens were installed across the spillway to keep the expensive game fish from escaping. The dam was lowered by a few feet so that two carriages could navigate the carriage road to the clubhouse. Relief pipes and valves that controlled the water level and spill off from the original dam were sold off for scrap, and rustic cottages were built nearby.

For the pleasure of their private members, club owners soon began modifications to the dam. Fish screens were installed across the spillway to keep the expensive game fish from escaping. The dam was lowered by a few feet so that two carriages could navigate the carriage road to the clubhouse. Relief pipes and valves that controlled the water level and spill off from the original dam were sold off for scrap, and rustic cottages were built nearby.

Ignored Warnings

Notoriously leaky, repairs to the earthen dam had been neglected for years. As torrential rains came down, swollen waters from the lake put tremendous pressure on the poorly maintained dam. With fish screens trapping debris that kept the spillway from flowing and with no other way to control the lake level, the water kept rising.

Club officials struggled to reinforce the earthen dam, but it continued to disintegrate. When the lake’s water began to pour over the top, it was apparent that a catastrophic collapse was inevitable and imminent. Frantic riders were sent down the valley to alert the local communities and tell them to evacuate. Sadly, few residents heeded the alarm being so often used to the minor seasonal flooding from the Little Conemaugh river.

Club officials struggled to reinforce the earthen dam, but it continued to disintegrate. When the lake’s water began to pour over the top, it was apparent that a catastrophic collapse was inevitable and imminent. Frantic riders were sent down the valley to alert the local communities and tell them to evacuate. Sadly, few residents heeded the alarm being so often used to the minor seasonal flooding from the Little Conemaugh river.

This time, however, the flood danger was much more serious and deadly.

On May 31, 1889 at 3:10pm, the South Fork Dam washed away, leaving a wake of destruction that killed 2,209 people and wiped the City of Johnstown off the map forever. It took only 10 minutes for the raging torrent of 20 million tons or about 4.8 billion gallons of water to rip through the communities of South Fork, Mineral Point, Woodvale, and East Conemaugh.

Along the way, the deluge accumulated everything in its path, including all sorts of debris—from city buildings, houses, and barns. Piles of boulders, trees, farm equipment, rolls of barbed wire, horse carriages, and railroad cars churned in the turmoil. Embroiled in the devastation were also animals and people—both dead and alive.

Along the way, the deluge accumulated everything in its path, including all sorts of debris—from city buildings, houses, and barns. Piles of boulders, trees, farm equipment, rolls of barbed wire, horse carriages, and railroad cars churned in the turmoil. Embroiled in the devastation were also animals and people—both dead and alive.

By the time the raging waters reached Johnstown at 4:07 pm, the mass of debris was a wave 45-feet-tall, nearly a half mile wide and traveling at 40 miles per hour.

Despite the shocking immensity of this tragedy, relief efforts to the ravaged communities began almost immediately. Emergency shelters for homeless residents popped up and the grim task of cleaning up began. Volunteers and donations poured in from across the country and world, sending tons of supplies and help. One of the first to arrive was Clara Barton, who had founded the American Red Cross just a few years earlier.

It would take months to sift through all the wreckage to find the bodies and years to fully recover from the aftermath.

It would take months to sift through all the wreckage to find the bodies and years to fully recover from the aftermath.

Lessons Learned

It is widely thought the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was to blame for the catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam. Members of the club neglected to properly maintain the dam and made numerous dangerous modifications. Lowering the dam crest to only about four feet above the spillway severely impaired the ability of the structure to withhold stormwater overflow. The missing discharge pipes and relief valves prevented the reservoir from being drained for repairs and the elaborate fish screens clogged the spillway with debris. The club had also been warned by engineers that the dam was unsafe.

A hydraulic analysis published in 2016 confirmed what had long been suspected, that the changes made to the dam by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club severely reduced the ability of the dam to withstand major storms.1

A hydraulic analysis published in 2016 confirmed what had long been suspected, that the changes made to the dam by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club severely reduced the ability of the dam to withstand major storms.1

The South Fork Dam was simply unable to withstand the large volume of stormwater that occurred on that fateful day on May 31, 1889.

Although the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club failed to maintain the dam, club members were never legally held responsible for the Johnstown Flood after successfully arguing that the disaster was an “act of God.”

Due to what many perceived as an injustice and outrage towards the wealthy club members, American law was ultimately challenged and “a non-negligent defendant could be held liable for damage caused by the unnatural use of land”. This legal action eventually imposed laws for the acceptance of strict liability for damages and loss.

National Dam Safety Awareness Day

On May 31st, we commemorate the catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam by recognizing this day as National Dam Safety Awareness Day.

The Johnstown flood or the Great Flood of 1889, as it was later known as, was the single deadliest disaster in the U.S at the time. This tragedy, 129 years later, is still a harsh reminder of the critical importance of the proper maintenance and safe operation of dams.

Earth embankment dams may fail due to overtopping by flood water, erosion of the spillway discharge channel, seepage, settling, and cracking or movement of the embankment.

Routine dam evaluations and inspections, as required by law, can identify problems with dams before conditions become unsafe. Dams embankments, gatehouses and spillways, like other structures, can deteriorate due to weather, vandalism, and animal activity. Qualified engineering firms can perform soil borings, soil testing, stability analyses, hydrologic and hydraulic modeling for evaluating spillway sizing and downstream hazard potential, arrange for under water inspections by divers, permitting, and assistance in applying for funding for repairs. Also required, are Emergency Action Plans (EAP) that identifies potential emergency conditions and specifies preplanned actions to be followed in the case of a dam failure to minimize property damage or loss of life.

The required frequency of dam inspections will vary depending on the state, but generally are based on hazard classification, with high hazard dams requiring more frequent inspection. Generally dam inspections should be performed every two years for high hazard dams, unless the state requires more frequent inspections. The best time of year for inspections is in the fall, when reservoir levels are typically low, and when foliage and tree leaves are reduced, allowing improved visibility around the dam.

A wealth of information on dam safety awareness, can be found at the Association of State Dam Safety Officials website

1Wikipedia.com