Funding Programs for Lead Service Line Replacement

In our line of work, we take pride in working to improve our drinking water and provide cost-effective, informative, and innovative project solutions when it comes to water. This pride and passion runs especially deep when it comes to lead exposure.

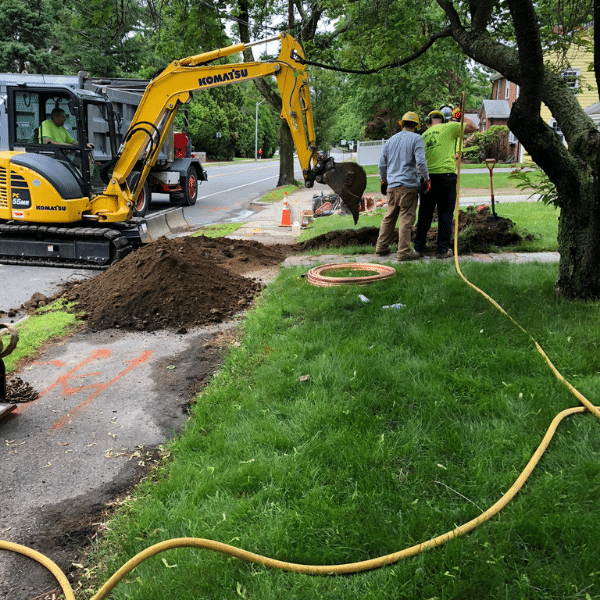

For example, in an effort to help remove lead pipes from Massachusetts turf, in the past we have partnered with the city of Marlborough, MA and replaced lead pipes with copper ones in approximately 250 homes, and have helped with the replacement of 427 services for the city of Newton, MA, among other cities and towns as well.

For example, in an effort to help remove lead pipes from Massachusetts turf, in the past we have partnered with the city of Marlborough, MA and replaced lead pipes with copper ones in approximately 250 homes, and have helped with the replacement of 427 services for the city of Newton, MA, among other cities and towns as well.

Like we said, this passion runs deep. And it is from this passion that we want to take a moment to discuss the Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (also known as “the Trust”) and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) joining forces to drive municipal participation in the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Lead and Copper Rule Revision (LCRR) to determine if public or private lead service lines (LSLs) contain lead. Their efforts have resulted in a $20 million grant for public water suppliers to complete their LSL inventory plan or design a LSL replacement program.

This is great news. But what makes it so great?

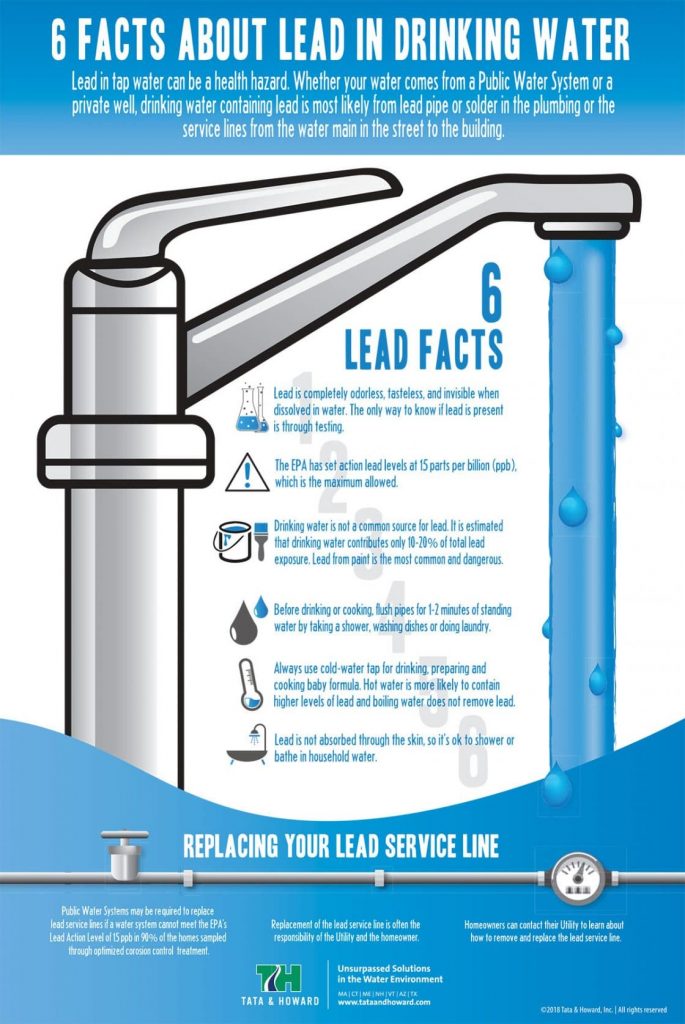

For starters, let’s start with why lead is bad for us. Exposing one to lead, whether by contaminated drinking water or ingestion, can lead to severe brain and nervous system damage, kidney damage, can drastically affect children and those who are pregnant, and can cause death.

For starters, let’s start with why lead is bad for us. Exposing one to lead, whether by contaminated drinking water or ingestion, can lead to severe brain and nervous system damage, kidney damage, can drastically affect children and those who are pregnant, and can cause death.

Prior to 1944, lead was commonly used in service lines, home pipes and paints, coins, and even dishes and cosmetics (yikes!). And in 1978, lead-based paints were banned for residential use; but it wasn’t until 1986 that Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act, prohibiting the use of pipes, solder, or flux that were not lead-free. Even so, it is reported that even today, 29.4% of all US homes contain lead hazards.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that every year, one million people die of lead poisoning. What’s worse is that the EPA estimates that there are between six and ten million lead service lines in this country. And of course, we can’t bring up drinking water pollution without bringing up Flint, MI, a city that went without safe drinking water from April 2014 to 2019, exposing between 6,000-12,000 children to severe lead poisoning and killing twelve people.

The gist is that lead is not our friend.

Now, what exactly is LSL replacement? It’s exactly how it sounds: it is a service line replacement for lead pipes where they are replaced with copper ones. All in all, LSL replacement is the only long-term solution to protecting the public from lead pipes.

Back to the main message: The Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (the Trust) and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) are offering $20 million in grants for assisting public water suppliers with completing planning projects for lead service line inventories and replacement programs.

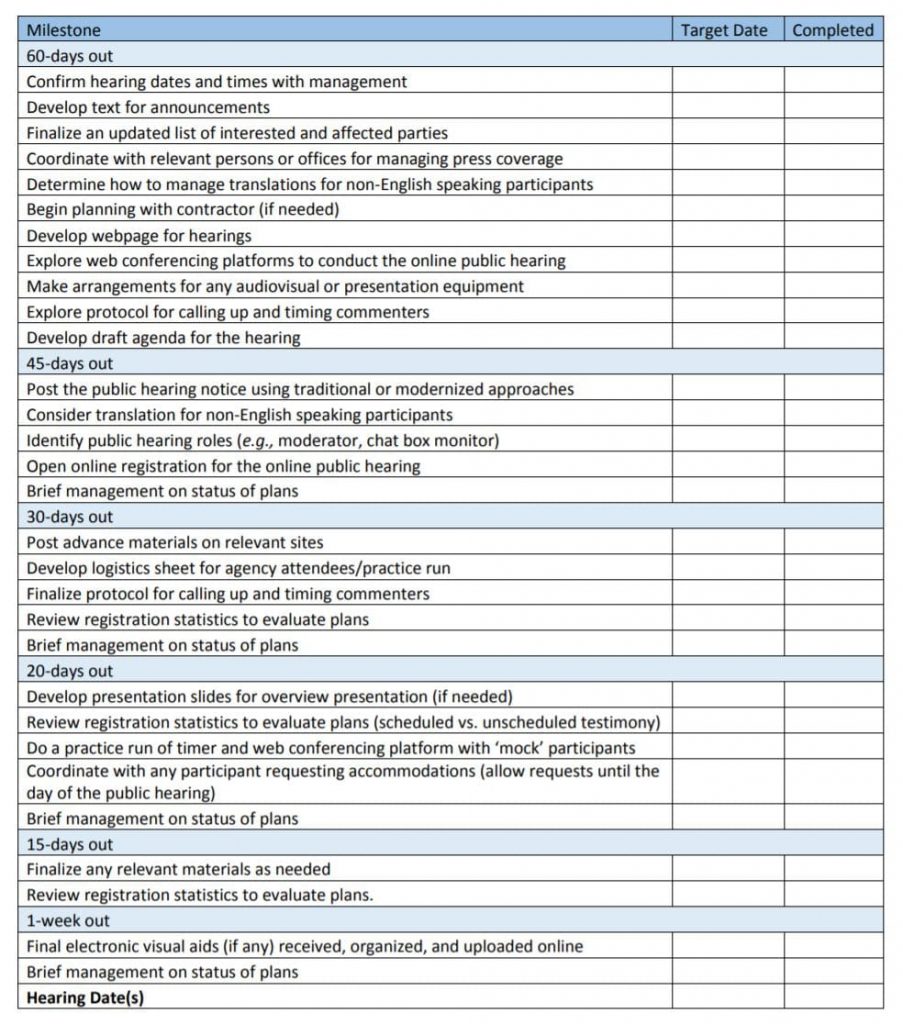

Need help constructing your LSL inventory plan? Our Vice President, Justine Carroll, shared a brief planning structure you can use when creating your application. Want more assistance? You can reach out at to us via phone or email. We are happy to help!

The deadline for the LSL inventory plans is October 16, 2024. MassDEP requires a submission of every municipality Public Water System’s (PWS) plan of action on prioritizing, funding, and fully removing any LSLs that are connected to their distribution system. In addition, municipalities that serve 50,000+ people must post their inventories on their website, allowing full transparency for both residents and businesses to access this information.

An excellent alternative if your PWS serves a population with less than 10,000 people is that MassDEP will “use $1.3 million of the set-asides from the DWSRF Lead Service Line Grant to contract with a qualified technical assistance provider to work with the PWS,” according to Mass.Gov. This means that small communities will be able to have access to a free consultant, paid for by MassDEP to help with the LSL planning.

You can read more about the LSL planning grant agreement here. And again, if you have any questions on this program or need help with applying for this funding, reach out to us today. We are just a phone call or email away.

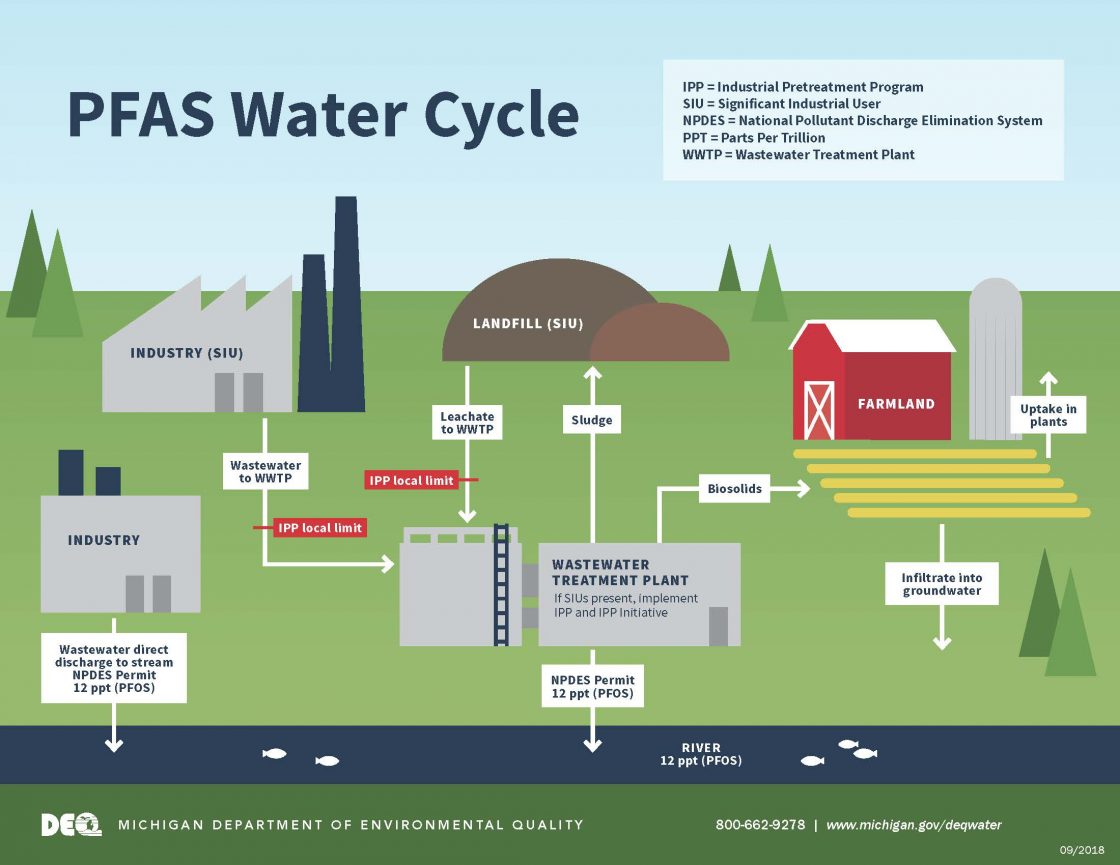

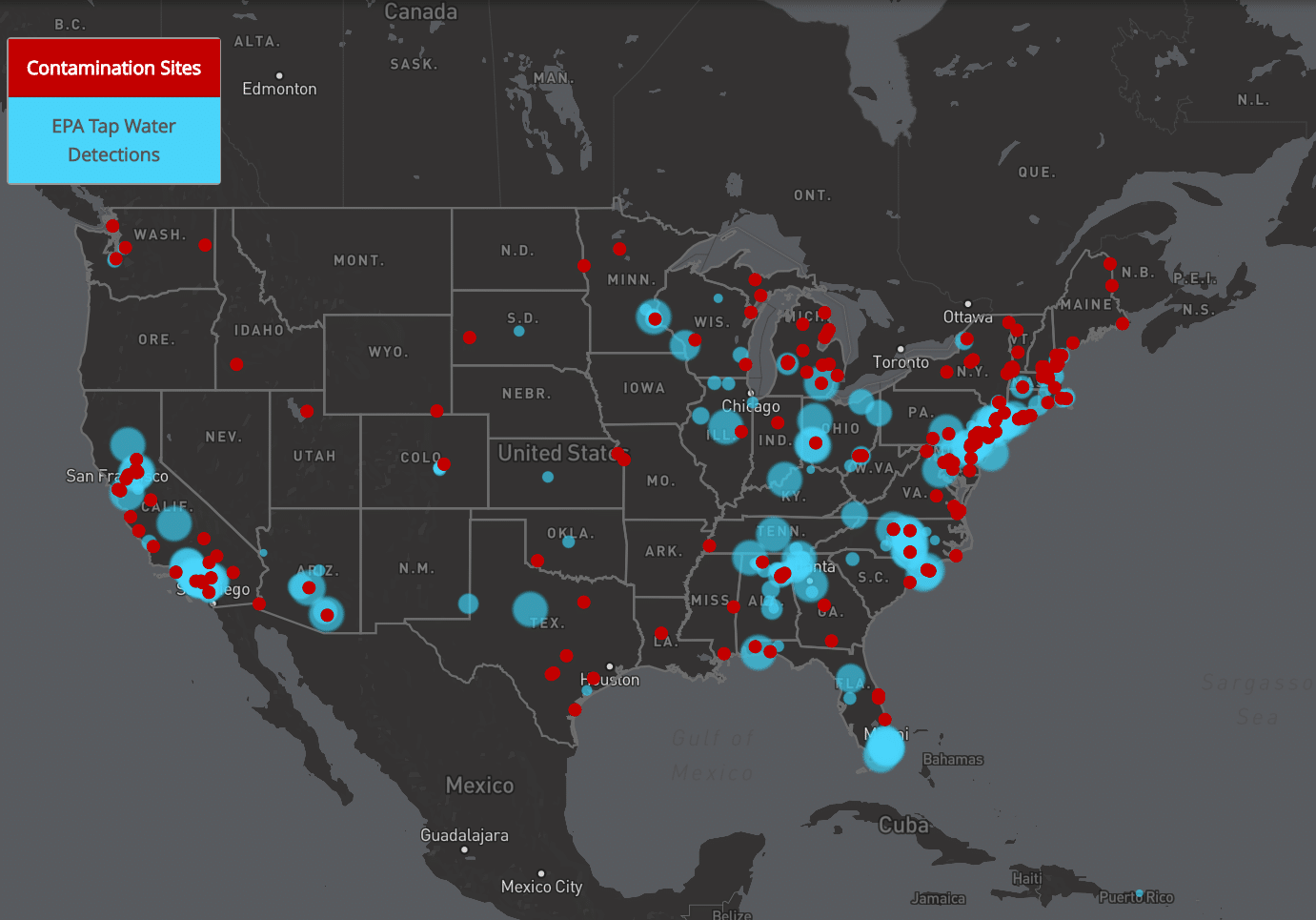

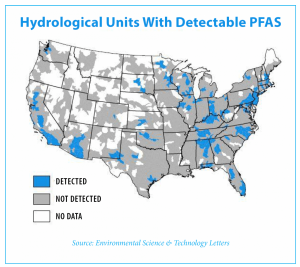

According the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), all these UCMR 3 PFAS compounds have been detected in public water supplies across the US. Since PFAS are considered emerging contaminants, there are currently no established regulatory limits for levels in drinking water. However, in 2016, the EPA set Health Advisory levels (HA) of 0.07 micrograms per liter (µg/L) or 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for the combined concentrations of two PFAS compounds, PFOS and PFOA.

According the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), all these UCMR 3 PFAS compounds have been detected in public water supplies across the US. Since PFAS are considered emerging contaminants, there are currently no established regulatory limits for levels in drinking water. However, in 2016, the EPA set Health Advisory levels (HA) of 0.07 micrograms per liter (µg/L) or 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for the combined concentrations of two PFAS compounds, PFOS and PFOA. The EPA also recommends that treatment be implemented for all five PFAS when one or more of these compounds are present.

The EPA also recommends that treatment be implemented for all five PFAS when one or more of these compounds are present. Most research on the effects of PFAS on human health is based on animal studies. And, although there is no conclusive evidence that PFAS cause cancer, animal studies have shown there are possible links. However, PFAS ill-health effects are associated with changes in thyroid, kidney and liver function, as well as affects to the immune system. These chemicals have also caused fetal development effects during pregnancy and low birth weights.

Most research on the effects of PFAS on human health is based on animal studies. And, although there is no conclusive evidence that PFAS cause cancer, animal studies have shown there are possible links. However, PFAS ill-health effects are associated with changes in thyroid, kidney and liver function, as well as affects to the immune system. These chemicals have also caused fetal development effects during pregnancy and low birth weights. Some of it can be recycled. Quite a bit ends up in the trash and landfills. And more than you can imagine ends up loose as plastic pollution, eventually making its way into our waterways. There are millions of tons of debris floating around in the water—and most of it is plastic. It is estimated that up to 80% of marine trash and plastic actually originates on land—either swept in from the coastline or carried to rivers from the streets during heavy rain via storm drains and sewer overflows.

Some of it can be recycled. Quite a bit ends up in the trash and landfills. And more than you can imagine ends up loose as plastic pollution, eventually making its way into our waterways. There are millions of tons of debris floating around in the water—and most of it is plastic. It is estimated that up to 80% of marine trash and plastic actually originates on land—either swept in from the coastline or carried to rivers from the streets during heavy rain via storm drains and sewer overflows. Drink from reusable containers and fill with tap water. Consider that close to 50 billion plastic bottles are tossed in the trash each year and only 23% are recycled!1 If that isn’t’ enough to convince you to stop buying ‘disposable’ water bottles, a recent study by

Drink from reusable containers and fill with tap water. Consider that close to 50 billion plastic bottles are tossed in the trash each year and only 23% are recycled!1 If that isn’t’ enough to convince you to stop buying ‘disposable’ water bottles, a recent study by

Not only healthier for you, cooking at home helps reduce the endless surplus of plastic packaging – take out containers, food wrappers, bottles, and eating utensils. Choose fresh fruits and veggies and bulk items with less packaging…and pack your leftovers or lunch in reusable containers and bags.

Not only healthier for you, cooking at home helps reduce the endless surplus of plastic packaging – take out containers, food wrappers, bottles, and eating utensils. Choose fresh fruits and veggies and bulk items with less packaging…and pack your leftovers or lunch in reusable containers and bags.

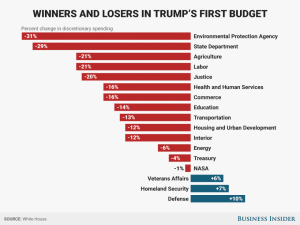

Trump’s proposed FY18 budget includes deep cuts to the nation’s major infrastructure programs. Both the DWSRF and CWSRF, funded by the EPA, are slated for drastic reduction under Trump’s budget, while the CBDG program is marked for elimination. In fact, Trump’s budget proposes to completely eliminate 66 federal programs including not only CBDG but also the United States Department of Agriculture’s Rural Water and Waste Disposal Program, and the Northern Border Regional Commission, which is a Federal-State partnership for economic and community development within the most distressed counties of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. Without these funding programs, some communities may not be able to implement needed system improvements.

Trump’s proposed FY18 budget includes deep cuts to the nation’s major infrastructure programs. Both the DWSRF and CWSRF, funded by the EPA, are slated for drastic reduction under Trump’s budget, while the CBDG program is marked for elimination. In fact, Trump’s budget proposes to completely eliminate 66 federal programs including not only CBDG but also the United States Department of Agriculture’s Rural Water and Waste Disposal Program, and the Northern Border Regional Commission, which is a Federal-State partnership for economic and community development within the most distressed counties of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. Without these funding programs, some communities may not be able to implement needed system improvements. Modern-day, developed nations use an exorbitant amount of chemicals for a variety of reasons. Some of these chemicals are used to prevent and treat illness, to reduce pain from injury or surgery, to treat mental health issues, and for hygiene, grooming, and cosmetic reasons. Commonly referred to as Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, or PPCPs, these products include prescription and over-the-counter medications, cosmetics, fragrances, face and body washes, sunscreens, insect repellants, and lotions.

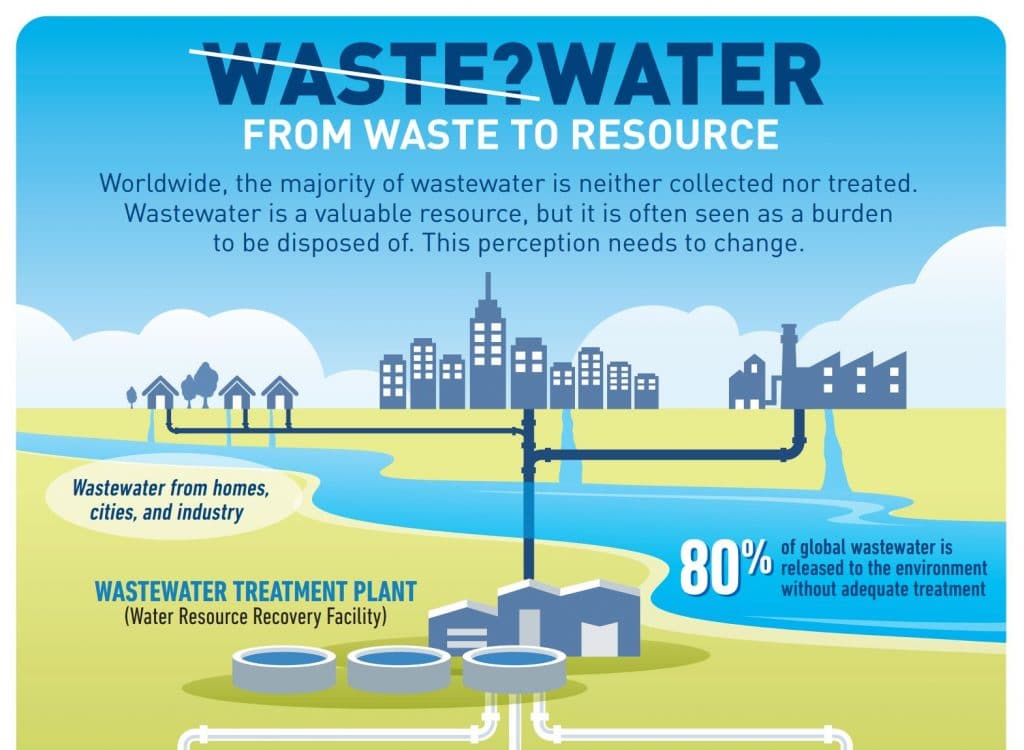

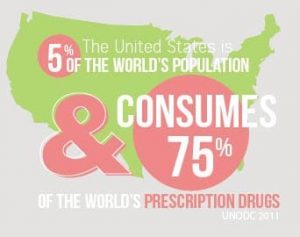

Modern-day, developed nations use an exorbitant amount of chemicals for a variety of reasons. Some of these chemicals are used to prevent and treat illness, to reduce pain from injury or surgery, to treat mental health issues, and for hygiene, grooming, and cosmetic reasons. Commonly referred to as Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, or PPCPs, these products include prescription and over-the-counter medications, cosmetics, fragrances, face and body washes, sunscreens, insect repellants, and lotions. PPCPs and EDCs enter our waterways through sewage, leachate from landfills and septic systems, flushing of unused medications, and agricultural runoff, and they have the potential to cause a myriad of problems. While there has not yet been a truly significant amount of research completed on all of these products and chemicals, some facts are known. For example, excessive antibiotic use has led to the development of “superbugs,” or bacteria such as MRSA that are resistant to most antibiotics.

PPCPs and EDCs enter our waterways through sewage, leachate from landfills and septic systems, flushing of unused medications, and agricultural runoff, and they have the potential to cause a myriad of problems. While there has not yet been a truly significant amount of research completed on all of these products and chemicals, some facts are known. For example, excessive antibiotic use has led to the development of “superbugs,” or bacteria such as MRSA that are resistant to most antibiotics.  Some of the most common EDCs in drinking water include estrogen and progesterone from birth control pills, as well as anabolic steroids. These compounds interfere with the reproductive capabilities of aquatic wildlife. Examples include eggshell thinning and subsequent reproductive failure of waterfowl; reduced populations of Baltic seals due to lower fertility and increased miscarriage; development of male reproductive organs in female marine animals, such as snails; feminization and subsequent decreased populations of certain types of fish, including bass; and reduced or malformed frog populations.

Some of the most common EDCs in drinking water include estrogen and progesterone from birth control pills, as well as anabolic steroids. These compounds interfere with the reproductive capabilities of aquatic wildlife. Examples include eggshell thinning and subsequent reproductive failure of waterfowl; reduced populations of Baltic seals due to lower fertility and increased miscarriage; development of male reproductive organs in female marine animals, such as snails; feminization and subsequent decreased populations of certain types of fish, including bass; and reduced or malformed frog populations. Currently, most PPCPs and EDCs are not regulated at either the state or federal level; however, they are being investigated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as Contaminants of Emerging Concern. Because PPCPs and EDCs appear to hinder reproduction in marine life, many state environmental organizations strongly support additional research and potential regulation on these compounds. In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to set drinking water and cleanup standards for the known EDC perchlorate after it had been detected in the state’s drinking water, and many states have implemented public education campaigns on these compounds, their effects, and their proper disposal.

Currently, most PPCPs and EDCs are not regulated at either the state or federal level; however, they are being investigated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as Contaminants of Emerging Concern. Because PPCPs and EDCs appear to hinder reproduction in marine life, many state environmental organizations strongly support additional research and potential regulation on these compounds. In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to set drinking water and cleanup standards for the known EDC perchlorate after it had been detected in the state’s drinking water, and many states have implemented public education campaigns on these compounds, their effects, and their proper disposal. On an individual level, taking small, simple steps can have a large impact on the amount of PPCPs and EDCs in our water supply:

On an individual level, taking small, simple steps can have a large impact on the amount of PPCPs and EDCs in our water supply: