Recently in the news, we have heard a lot about the nationwide lead in drinking water crisis and the need to update our aging infrastructure. In addition, the plight of the people living in Navajo Nation has been brought to the nation’s attention after being showcased in a video by CBS Sunday Morning News. However, there is yet another very serious water crisis in the United States that has garnered very little media attention, and this week, we will be concluding our four-part series on water crises in the United States by talking about colonias.

Recently in the news, we have heard a lot about the nationwide lead in drinking water crisis and the need to update our aging infrastructure. In addition, the plight of the people living in Navajo Nation has been brought to the nation’s attention after being showcased in a video by CBS Sunday Morning News. However, there is yet another very serious water crisis in the United States that has garnered very little media attention, and this week, we will be concluding our four-part series on water crises in the United States by talking about colonias.

What Are Colonias?

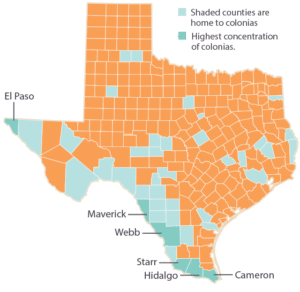

Colonia translates to neighborhood in Spanish, and in the United States, colonias are primarily Hispanic neighborhoods found along the Mexican border in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas. With over 2,200 colonias, Texas has by far the most colonias in the nation, as well as the largest colonia population with over 500,000 residents. The modern-day colonia population is about 96% Mexican-American, with about 74% of those — and 94% of colonia children — being American citizens.

Colonias originated in the 1950s. At this time, less than honorable developers bought up worthless land along the Mexican border — such as land that was agriculturally useless or located in flood plains — parceled it into tiny lots with little to no infrastructure and sold it off to low-income immigrants in search of affordable housing. To this day, colonias are often bought through a contract for deed, which is a questionable financing method by which developers offer low down and monthly payments with a very high interest rate and no title until the loan is paid in full. Prior to 1995, developers did not typically record the transactions with the county clerk, leaving the buyer with virtually no rights. If they fell behind on payments, the developer could repossess the property quickly, usually within just 45 days, without going through the foreclosure process.

Fortunately, Texas passed the Colonias Fair Land Sales Act in 1995 to somewhat protect colonia residents who are forced to finance through a contract for deed. The Act requires developers to record the contract with the county clerk and to provide property owners with an annual statement that shows the amount paid towards the loan and taxes as well as the number of remaining payments. The Act also forces developers to itemize which services, such as water, wastewater, and electricity, are available, and whether the land is located in a flood plain.

Fortunately, Texas passed the Colonias Fair Land Sales Act in 1995 to somewhat protect colonia residents who are forced to finance through a contract for deed. The Act requires developers to record the contract with the county clerk and to provide property owners with an annual statement that shows the amount paid towards the loan and taxes as well as the number of remaining payments. The Act also forces developers to itemize which services, such as water, wastewater, and electricity, are available, and whether the land is located in a flood plain.

While the Colonias Fair Land and Sales Act has improved contract for deed sales, there remain serious problems. Because property owners do not actually own the land or have a title, they cannot secure any type of financing that uses the property as collateral. Considering that colonia residents are typically well below the poverty level, any other types of financing are also unavailable to them, making it impossible to improve their property. Therefore, colonia residents typically construct their homes in drawn out phases as funds become available to them. Because of this, colonia homes often do not have electricity or even basic plumbing.

Challenges in Colonias

Arguably the most serious challenge facing colonias is the lack of improved water and sanitation services. Many colonias do not have public sewer systems and instead rely on rudimentary septic systems or outhouses that are often inadequate and overflow. And because the land is frequently in flood plains with poorly constructed roads that do not properly drain, sewage collects and pools, rife with bacteria and pathogens. Even colonias that do have sewer systems typically lack any type of wastewater treatment. Therefore, untreated wastewater is discharged into local streams that flow directly into the Rio Grande or the Gulf of Mexico.

www.wendyjepson.net

Potable water also presents a challenge to colonia residents. Very often, inhabitants must buy water in drums to meet their needs, or, even worse, they utilize untreated water from wells that are contaminated. Some private companies have installed water “vending machines” that provide bottled water at an astronomical cost to residents who can ill afford it. Even colonias that do have water lines have major problems, because residents are unable to tie-in due to their homes not meeting county building codes; to meet the building codes, they need to have adequate plumbing — a true Catch-22 situation. In fact, housing in colonias is typically considered dilapidated by local inspectors. Residents often start with just tents, cardboard, and lean-tos, and make improvements little by little as funds allow.

Due to the lack of improved water and sanitation, as well as lack of electrical services, it should come as little surprise that health conditions in colonias are often deplorable. Hepatitis A, dysentery, tuberculosis, cholera, salmonella, and other diseases occur at an astronomically higher rate in colonias than they do in the rest of Texas, according to Texas Department of Health data. To make matters worse, most colonias do not have local medical services and have a serious shortage of primary care providers, and most colonia residents lack health insurance. Therefore, the average age of colonia residents is only 27 — a full 10 years younger than the national average. And, just as is the case in Africa and other developing areas, quality of health is directly linked to quality of education. Therefore, many colonia residents remain undereducated — 55% of residents do not have a high school diploma — causing the cycle of poverty to continue generationally. The unemployment rate in colonias is anywhere from 20-60%, compared with 7% for the rest of Texas.

Assistance to Colonias

Thankfully, through a series of public outreach initiatives, more attention has been brought to the existence of colonias and the third-world conditions in them. In the last 20 years, the Texas Secretary of State has been recording the infrastructure, or lack thereof, within colonias and providing a significant amount of funding — tens of millions of dollars — to improve these areas. And it is working, albeit slowly. Since 2006, about 100 colonias have been moved out of the “red” category, indicating the worst conditions. However, with over 2,200 colonias along the Texas-Mexico border, there is still much work to be done.

On a federal level, USDA Rural Development has grants available through the Individual Water and Wastewater Program for households residing in an area recognized as a colonia before October 1, 1989. The colonia must be located in a rural area and determined to be a colonia on the basis of objective criteria including lack of potable water supply, lack of adequate sewage systems, lack of decent, safe and sanitary housing, and inadequate roads and drainage. Grant funds may be used to connect service lines to a residence, pay utility hook-up fees, install plumbing and related fixtures like a bathroom sink, bathtub or shower, commode, kitchen sink, water heater, outside spigot, or bathroom, if lacking. Qualifying applicants must own and occupy their home, show income from all individuals residing in the home below the most recent poverty income guidelines, and not be delinquent on any Federal debt. The maximum individual grant for water systems is $3,500 and for wastewater is $4,000 with a lifetime assistance maximum not to exceed $5,000 per individual. Further information can be found on USDA’s web site. In addition, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in Texas, Arizona, California, and New Mexico has set aside up to 10 percent of their State Community Development Block Grant Program (CDBG) funds for improving living conditions for colonias residents.

Fortunately, colonia residents are a very resourceful, tight knit group who are willing to work together and help each other, and some private and non-profit institutions have also become involved in the plight of colonia residents. For example, Texas A&M worked with residents on a water filtration project which involved making simple filters to make water potable. In addition, a non-profit lender called the LiftFund has provided loans to some colonia residents to assist them with starting a business. These loans have a very low interest rate and are given to people who cannot qualify for a traditional loan. Colonia residents are very often entrepreneurial in spirit, perhaps through necessity. After all, for years they have done what they need to do to get by, whether it be selling handmade crafts at flea markets or cutting up tires dumped along colonia roads and turning them into unique flower pots.

In Conclusion

Colonias are a little known part of America that have conditions oftentimes no better than those found in developing countries. One of the biggest causes of generational poverty in colonias is attributed to lack of basic water and sanitation services, causing health and education issues. Just like the plight of the people living in Navajo Nation, it is shameful that people living in the richest land in the world do not have access to these basic human rights. Add to this the lack of charitable organizations supporting water poverty in the United States, and colonias qualify as one of the most significant, and heartbreaking, water crises in the nation.