After the common cold, tooth decay is said to be mankind’s second most common disease. Because the mouth is a primary entryway into the body, bacteria caused by poor oral health, can easily enter the bloodstream and cause infection and inflammation wherever it spreads. From arthritis to dementia and cardiovascular disease to diabetes—all these ailments, and many more, have been associated with poor oral health.

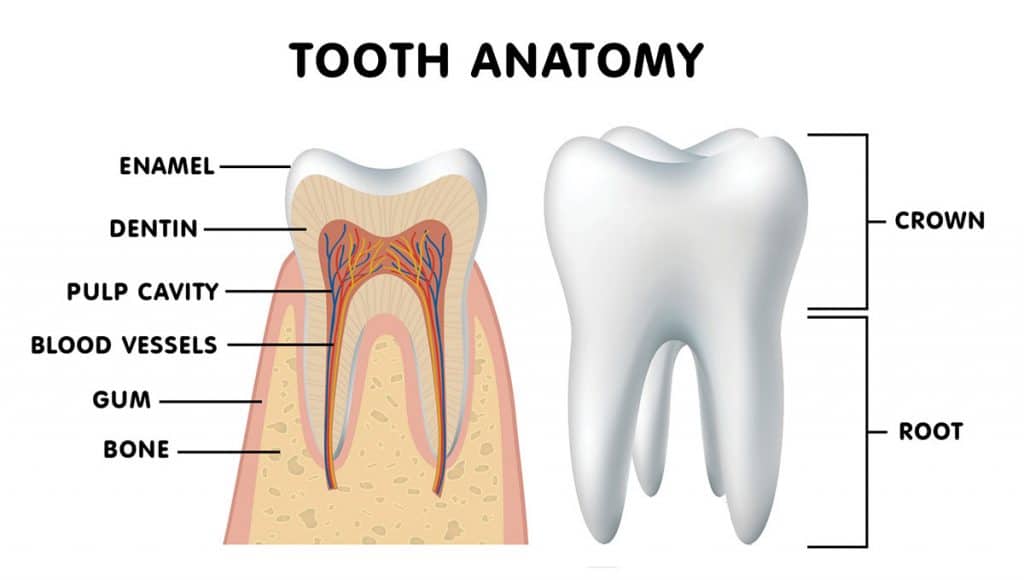

Even so, that millimeter of enamel making up the outer part of the tooth is the hardest substance of the human body and can outlast even the human skeleton when interred. In fact, the oldest vertebrate fossil relics going back 500 million years are teeth. Despite these details, teeth can be surprisingly fragile and prone to decay.

Even so, that millimeter of enamel making up the outer part of the tooth is the hardest substance of the human body and can outlast even the human skeleton when interred. In fact, the oldest vertebrate fossil relics going back 500 million years are teeth. Despite these details, teeth can be surprisingly fragile and prone to decay.

Our teeth and gums, so often taken for granted, have until as recently as the mid-twentieth century, a very interesting and painful past.

A Toothless History

Tooth decay is not merely a modern disease; scientists have discovered mankind has suffered from dental disease throughout history. During the early years of human history, evidence shows ancient hunter-gatherers did not suffer too greatly from tooth decay. Rather, the shift in poor oral health occurred with the transition to agricultural societies and the introduction of crops that were high in carbohydrates and sugars. The consumption of these bacteria-causing foods destroyed tooth enamel.

That change in diet was the beginning of centuries of barbarous dentistry and a mouthful of pain.

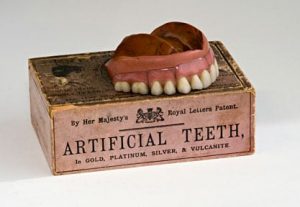

Young or old, rich or poor—no one was immune to the ravages of toothaches, swollen bleeding gums, and tooth loss. It wasn’t until the reign of Louis XIV in the early 17th century, when fashionable society demanded—more for appearance than for eating—solutions for missing teeth. With that, Pierre Fauchard, who was to be called the “Father of Dentistry,” introduced a new era of dental care. He not only practiced more humane tooth extraction, he also developed the first dental drill and methods for filling cavities, learned to fill a root canal, and introduced a spring to the upper portion of his ivory-carved dentures to keep them in place.

Still, with these advances in dentistry, tooth loss and decay persisted. Since ancient times, it was widely thought that toothaches were caused by worms that destroyed teeth. It wasn’t until 1890, when a dentist named Willoughby Miller identified that tooth decay was caused by a certain type of bacteria that thrives on sugar, creating an acid that ate away at tooth enamel.

Still, with these advances in dentistry, tooth loss and decay persisted. Since ancient times, it was widely thought that toothaches were caused by worms that destroyed teeth. It wasn’t until 1890, when a dentist named Willoughby Miller identified that tooth decay was caused by a certain type of bacteria that thrives on sugar, creating an acid that ate away at tooth enamel.

But preventing tooth decay was still a mystery.

Brown-Stained Teeth

Dentists in Colorado wondered why their patients had mottled, discolored teeth. The cause of the brown-stained tooth enamel, it was discovered, was from high levels of fluoride in the water supply. Dr. Frederick McKay, the dentist spearheading this research, found that teeth afflicted by the “Colorado Brown Stain,” as it was called, were surprisingly resistant to decay.

Fluoride, which is a component of tooth enamel, is also found naturally in many foods we eat and is detected in water supplies around the world—as it was in water supplies to the small Colorado towns of Dr. McKay’s research. At low concentrations, fluoride can be beneficial to healthy teeth. However, too much exposure can have adverse effects, such as dental fluorosis, which causes tooth enamel to become mottled and stained.

Fluoride in Water and Other Sources

By the early 1930s, Dr. H. Trendley Dean, head of the Dental Hygiene Unit at the National Institute of Health (NIH) began investigating the prevalence of dental fluorosis, and exposure to fluoride in drinking water. After considerable debate, on the afternoon of January 25, 1945, powdered sodium fluoride was added to the Grand Rapid’s municipal water supply in Michigan.

Dentists stress that fluoride strengthens the tooth enamel, making it more resistant to tooth decay and thereby can greatly help dental health. However, most people now receive fluoride in their dental products, such as toothpaste, gels, and mouth rinses.