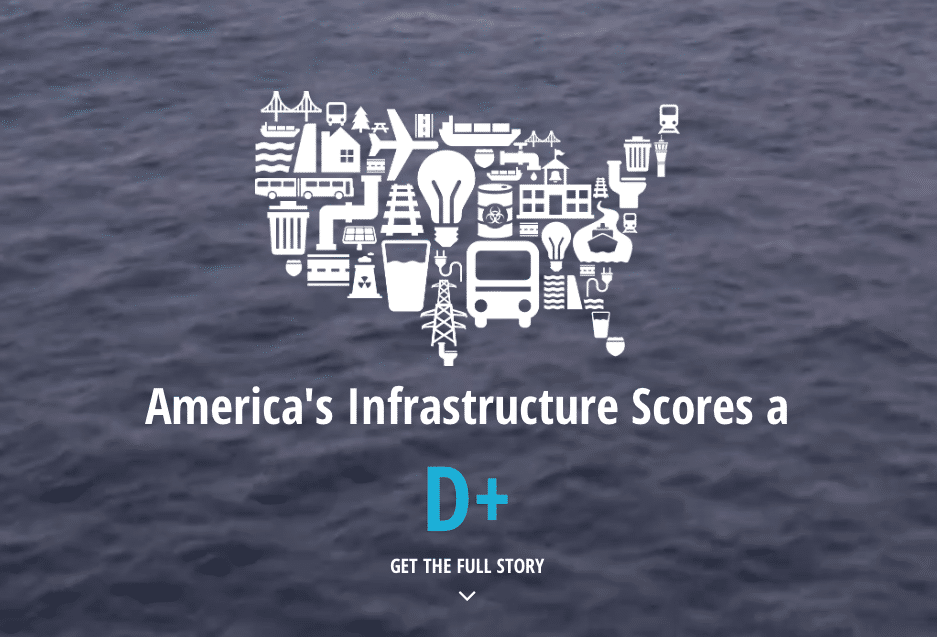

It is well known that our nation’s infrastructure is in desperate need of repair or replacement. In fact, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ACSE) 2017 Report Card has given our country’s infrastructure an overall grade of D+. Dams are a part of that critical infrastructure, and they have received an abysmal D grade from ASCE. We have over 90,000 dams in our country, and the average age of these dams is 56 years old. Considering that dams built 50 years ago were not designed for current standards and usually have inadequate spillway capacity, these numbers are concerning.

It is well known that our nation’s infrastructure is in desperate need of repair or replacement. In fact, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ACSE) 2017 Report Card has given our country’s infrastructure an overall grade of D+. Dams are a part of that critical infrastructure, and they have received an abysmal D grade from ASCE. We have over 90,000 dams in our country, and the average age of these dams is 56 years old. Considering that dams built 50 years ago were not designed for current standards and usually have inadequate spillway capacity, these numbers are concerning.

Even more alarming, America has nearly 15,500 high-hazard dams, with over 2,170 of these being deemed deficient. A dam is rated high-hazard when dam failure could result in the loss of human life, and deficient when it is at serious risk of failure. A deficient, high-hazard dam is a tragedy waiting to happen. Also, considering the estimated cost to repair these deficient, high-hazard dams is almost $45 billion, it is apparent that we have a dam crisis on our hands.

About Dams

Dams provide significant economic and social benefits to society, including flood control, water storage, irrigation, debris control, and navigation. In addition, around 3% of our nation’s dams provide hydroelectric power — a clean, renewable energy source — accounting for 35% of our country’s renewable energy and 10% of our total power needs. And, of course, the most frequent function of dams is recreation. Dams impound eight of the top ten most popular vacation lakes in the United States, accounting for millions of tourist dollars and some of our country’s most beautiful and enjoyable areas.

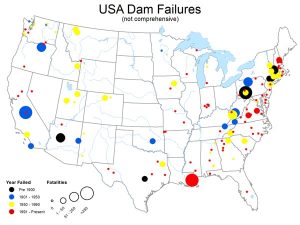

Catastrophic dam failures have occurred in the United States for well over a century, resulting in the deaths of thousands of people and causing millions of dollars in damages. This year, we narrowly avoided a disaster when California’s Oroville Dam stabilized after threatening to fail. During the crisis, over 188,000 people were displaced due to mandatory evacuations of the area. Although the Oroville Dam crisis thankfully ended without loss of life, the cost to repair the spillway is estimated to be $275 million. In 2003, the Silver Lake Dam in Michigan failed, causing approximately $100 million in property damages and putting over a thousand miners out of work. In 2004, the Big Bay Lake Dam in Mississippi failed, destroying 48 homes and seriously damaging 53 others. In 2006, the Ka Loko Dam in Hawaii failed, killing seven people and releasing nearly 400 million gallons of water, causing significant property and environmental damage.

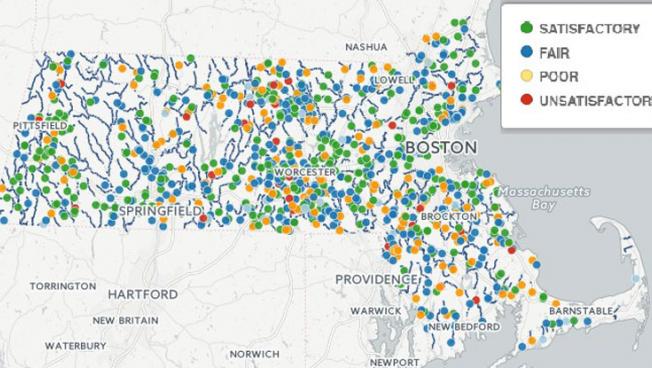

High-hazard dams are cause for concern in every state in the nation. In Massachusetts, 1,453 dams are included in the National Inventory of Dams, 333 of which are high-hazard. Of those, about 50 are classified as “poor” or “unsatisfactory” and in urgent need of repair. If any of these dams were to fail, there is a high likelihood that there would be a loss of human life. Dam failure is most frequently caused by overtopping, accounting for 34% of all dam failures. Causes of overtopping include inadequate spillway design, blocked spillways, settlement of the dam crest, and floods exceeding dam capacity. Other causes of dam failure include foundation defects such as slope instability and settlement (30%); piping, resulting in internal erosion caused by seepage (20%); and other causes including structural failure of materials, settlement and resulting cracking, poor maintenance, and acts of sabotage (16%).

Safety Programs

The National Dam Safety Program (NDSP) was signed into law in 1996. NDSP was established to improve safety and security around dams by providing assistance grants to state dam safety agencies to assist them in improving their regulatory programs; funding research to enhance technical expertise as dams are built and rehabilitated; establishing training programs for dam safety inspectors; and creating a National Inventory of Dams. Every state in the nation excepting Alabama has a dam safety program, and 41 states also have Emergency Action Plan (EAP) requirements. A detailed and up-to-date EAP is critical to a successful dam safety program for high-hazard and significant-hazard dams. States without EAP requirements are Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, North Carolina, Vermont, Wyoming, and — believe it or not — California.

Unfortunately, about one-third of our nation’s high-hazard dams lack an EAP. In addition, state dam safety programs are sorely underfunded and understaffed, and many of our nation’s deficient dams are not being repaired or rehabilitated in a timely manner. Why? State dam safety programs provide the inspection, permitting, recommendations, and enforcement authority for 80% of our nation’s dams, yet the average ratio of dams to dam safety inspectors is 207:1. Also, about two-thirds of our nation’s dams are privately-owned. Without enforcement of repair recommendations, some dam owners simply choose not to sink any money into their deficient dam.

For example, the Ka Loko Dam in Hawaii was privately-owned, and owner James Pflueger was sentenced to seven months in prison in exchange for a plea of no contest to reckless endangering. By entering the plea, prosecutors agreed to drop the seven counts of manslaughter. But admittedly, the dam failure was the result of a series of negligent events. The State of Hawaii, like most states in the nation, had a shortage of dam inspectors, and the Ka Loko Dam had not been adequately inspected. Also, Pflueger performed unpermitted construction activities at the dam, including grading and filling in the spillway. The County of Kauai ordered Pflueger to cease and desist all illegal grading operations, yet Pflueger ignored the order with help from then-Mayor Maryann Kusaka, who served as mayor of Kauai from 1997-2004. He also knew that there was seepage at the dam prior to the failure.

Key Issues

Clearly, the Ka Loko Dam failure was due to gross negligence and was completely avoidable. To avoid similar tragedies in the future, all of the key issues facing our nation’s dams should be addressed. First and foremost, our country needs to invest in infrastructure and to prioritize funding of dam safety programs. It is imperative that dam safety agencies have adequate personnel and resources to enforce inspection, repair, and rehabilitation recommendations. Also, since two-thirds of our nation’s dams are privately-owned, lack of funding for private dam upgrades is a huge problem. Adequate maintenance and rehabilitation of dams is costly, ranging from thousands to millions of dollars, and many private owners simply cannot afford these costs. Because of the high risk of high-hazard dams, our nation must prioritize funding assistance and loan programs to both public and private owners. It is also crucial that high-hazard dams have an up-to-date EAP, including action plans as well as notification and evacuation procedures, so that authorities are prepared and residents living downstream of the dam are protected. And speaking of residents, public outreach and awareness may be the most critical component of dam safety and awareness. The typical American citizen has no understanding of the role that dams play in our lives, or of the devastation that could come about from a dam failure. Even developers and officials are often in the dark about dams in their own communities. And, of course, everyone needs to understand that all high-hazard dams, no matter how seemingly structurally sound, are potentially dangerous and that there is inherent risk living in a dam break flood-prone area. Also, many of the private dam owners in our country are largely unaware of both their responsibility toward residents and businesses located downstream of their dam and of proper dam maintenance and repair procedures.

In Conclusion

We must change the way we manage our nation’s dams in order to prevent future catastrophes. The recent Oroville Dam crisis should serve as a warning to residents and legislators. As our dams age and climate change increases severe weather events, we must invest in the oversight, funding, and awareness of this critical infrastructure. Until we do, events such as the Oroville Dam crisis and the Ka Loko Dam failure may occur with increasing frequency, resulting in loss of life, environmental damage, and economic disaster.