Funding Programs for Lead Service Line Replacement

In our line of work, we take pride in working to improve our drinking water and provide cost-effective, informative, and innovative project solutions when it comes to water. This pride and passion runs especially deep when it comes to lead exposure.

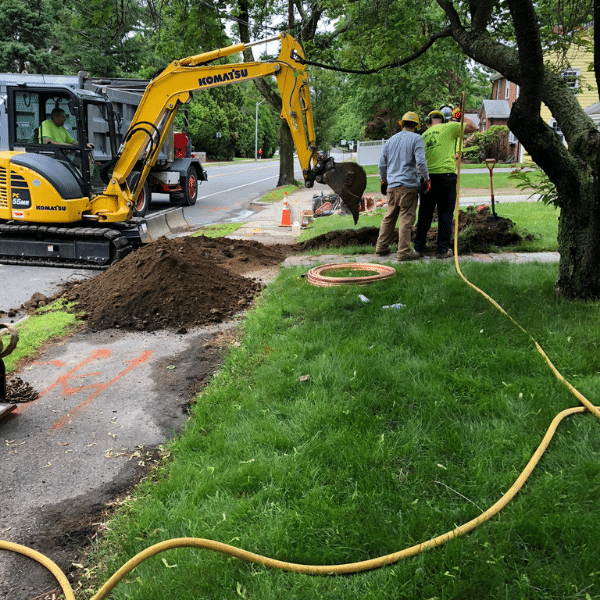

For example, in an effort to help remove lead pipes from Massachusetts turf, in the past we have partnered with the city of Marlborough, MA and replaced lead pipes with copper ones in approximately 250 homes, and have helped with the replacement of 427 services for the city of Newton, MA, among other cities and towns as well.

For example, in an effort to help remove lead pipes from Massachusetts turf, in the past we have partnered with the city of Marlborough, MA and replaced lead pipes with copper ones in approximately 250 homes, and have helped with the replacement of 427 services for the city of Newton, MA, among other cities and towns as well.

Like we said, this passion runs deep. And it is from this passion that we want to take a moment to discuss the Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (also known as “the Trust”) and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) joining forces to drive municipal participation in the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Lead and Copper Rule Revision (LCRR) to determine if public or private lead service lines (LSLs) contain lead. Their efforts have resulted in a $20 million grant for public water suppliers to complete their LSL inventory plan or design a LSL replacement program.

This is great news. But what makes it so great?

For starters, let’s start with why lead is bad for us. Exposing one to lead, whether by contaminated drinking water or ingestion, can lead to severe brain and nervous system damage, kidney damage, can drastically affect children and those who are pregnant, and can cause death.

For starters, let’s start with why lead is bad for us. Exposing one to lead, whether by contaminated drinking water or ingestion, can lead to severe brain and nervous system damage, kidney damage, can drastically affect children and those who are pregnant, and can cause death.

Prior to 1944, lead was commonly used in service lines, home pipes and paints, coins, and even dishes and cosmetics (yikes!). And in 1978, lead-based paints were banned for residential use; but it wasn’t until 1986 that Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act, prohibiting the use of pipes, solder, or flux that were not lead-free. Even so, it is reported that even today, 29.4% of all US homes contain lead hazards.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that every year, one million people die of lead poisoning. What’s worse is that the EPA estimates that there are between six and ten million lead service lines in this country. And of course, we can’t bring up drinking water pollution without bringing up Flint, MI, a city that went without safe drinking water from April 2014 to 2019, exposing between 6,000-12,000 children to severe lead poisoning and killing twelve people.

The gist is that lead is not our friend.

Now, what exactly is LSL replacement? It’s exactly how it sounds: it is a service line replacement for lead pipes where they are replaced with copper ones. All in all, LSL replacement is the only long-term solution to protecting the public from lead pipes.

Back to the main message: The Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (the Trust) and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) are offering $20 million in grants for assisting public water suppliers with completing planning projects for lead service line inventories and replacement programs.

Need help constructing your LSL inventory plan? Our Vice President, Justine Carroll, shared a brief planning structure you can use when creating your application. Want more assistance? You can reach out at to us via phone or email. We are happy to help!

The deadline for the LSL inventory plans is October 16, 2024. MassDEP requires a submission of every municipality Public Water System’s (PWS) plan of action on prioritizing, funding, and fully removing any LSLs that are connected to their distribution system. In addition, municipalities that serve 50,000+ people must post their inventories on their website, allowing full transparency for both residents and businesses to access this information.

An excellent alternative if your PWS serves a population with less than 10,000 people is that MassDEP will “use $1.3 million of the set-asides from the DWSRF Lead Service Line Grant to contract with a qualified technical assistance provider to work with the PWS,” according to Mass.Gov. This means that small communities will be able to have access to a free consultant, paid for by MassDEP to help with the LSL planning.

You can read more about the LSL planning grant agreement here. And again, if you have any questions on this program or need help with applying for this funding, reach out to us today. We are just a phone call or email away.

October 23-29 is National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2016. Established in 1999 by the U.S. Senate, National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week (NLPPW) occurs every year during the last week in October and is now supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the World Health Organization (WHO). This year’s NLPPW theme of “Lead-Free Kids for a Healthy Future” underscores the importance of protecting our future by educating the public about the dangers and sources of lead poisoning and what can be done to prevent it. While lead-based paint is arguably the most common and hazardous source of lead exposure for young children,

October 23-29 is National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2016. Established in 1999 by the U.S. Senate, National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week (NLPPW) occurs every year during the last week in October and is now supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the World Health Organization (WHO). This year’s NLPPW theme of “Lead-Free Kids for a Healthy Future” underscores the importance of protecting our future by educating the public about the dangers and sources of lead poisoning and what can be done to prevent it. While lead-based paint is arguably the most common and hazardous source of lead exposure for young children,

Lead in drinking water cannot be detected through taste or smell, and the only way to know for certain if your drinking water has elevated lead levels is to have your water professionally tested. Typically, lead pipes are found in homes that were built prior to 1986 and in older cities. Older homes with private wells are also at risk of having lead in drinking water. While

Lead in drinking water cannot be detected through taste or smell, and the only way to know for certain if your drinking water has elevated lead levels is to have your water professionally tested. Typically, lead pipes are found in homes that were built prior to 1986 and in older cities. Older homes with private wells are also at risk of having lead in drinking water. While

While utilities are working diligently to keep our nation’s water lead-free, public schools have recently come under fire, as schools from cities across the nation — including Boston, Massachusetts; Ithaca, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Tacoma, Washington — have found lead in their drinking water above the EPA’s action level of 15 parts per billion. Surprisingly, this contamination is the result of a legal loophole that many states are looking to close: schools are mandated by the EPA to be connected to a water supply that is regularly tested for lead and other contaminants; however, these utilities are not typically required to actually test the water inside the schools themselves. Considering that the average age of a school in the United States is 44 years old, it should come as no surprise that there are elevated levels of lead in the drinking water of public schools. After all, lead pipes were legal until about 30 years ago, and faucets and fixtures were allowed to contain up to 8% lead until 2014.

While utilities are working diligently to keep our nation’s water lead-free, public schools have recently come under fire, as schools from cities across the nation — including Boston, Massachusetts; Ithaca, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Tacoma, Washington — have found lead in their drinking water above the EPA’s action level of 15 parts per billion. Surprisingly, this contamination is the result of a legal loophole that many states are looking to close: schools are mandated by the EPA to be connected to a water supply that is regularly tested for lead and other contaminants; however, these utilities are not typically required to actually test the water inside the schools themselves. Considering that the average age of a school in the United States is 44 years old, it should come as no surprise that there are elevated levels of lead in the drinking water of public schools. After all, lead pipes were legal until about 30 years ago, and faucets and fixtures were allowed to contain up to 8% lead until 2014. Many states have introduced legislation this year that would require public schools to regularly test their water. Bills on the table in Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Rhode Island would require regular testing, as would a New York bill that takes it one step further by providing funding for said testing. In addition, the New York bill would require schools to notify parents and to provide an alternate supply of safe drinking water to students if elevated lead levels are found. In Massachusetts, all community water systems are required by Massachusetts drinking water regulations to collect lead and copper samples from at least two schools or early education and care program facilities that they serve in each sampling period, when they collect their Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) samples. In addition, in April of 2016, it was announced that $2 million from the Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (MCWT) will fund cooperative efforts to help Massachusetts public schools test for lead and copper in drinking water. The funds, to be used by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), will provide technical assistance to ensure that public school districts can sample the taps and water fountains in their schools, and to identify any results that show lead and copper contamination over the action level. On a federal level, legislation has been introduced to Congress that would requires states to assist schools with testing for lead; however, it does not provide funding.

Many states have introduced legislation this year that would require public schools to regularly test their water. Bills on the table in Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Rhode Island would require regular testing, as would a New York bill that takes it one step further by providing funding for said testing. In addition, the New York bill would require schools to notify parents and to provide an alternate supply of safe drinking water to students if elevated lead levels are found. In Massachusetts, all community water systems are required by Massachusetts drinking water regulations to collect lead and copper samples from at least two schools or early education and care program facilities that they serve in each sampling period, when they collect their Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) samples. In addition, in April of 2016, it was announced that $2 million from the Massachusetts Clean Water Trust (MCWT) will fund cooperative efforts to help Massachusetts public schools test for lead and copper in drinking water. The funds, to be used by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), will provide technical assistance to ensure that public school districts can sample the taps and water fountains in their schools, and to identify any results that show lead and copper contamination over the action level. On a federal level, legislation has been introduced to Congress that would requires states to assist schools with testing for lead; however, it does not provide funding.