Often in times of innovation, we as a society face unintended consequences. One that has held our attention for quite some time is the presence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in our water sources. PFAS are commonly found in everyday products and have made their way into our water supplies, posing a significant threat to public health.

In the ongoing battle against PFAS, water utilities have found themselves on the front lines, battling mitigation efforts, a lack of funding, and a complex web of responsibilities.

Understanding PFAS

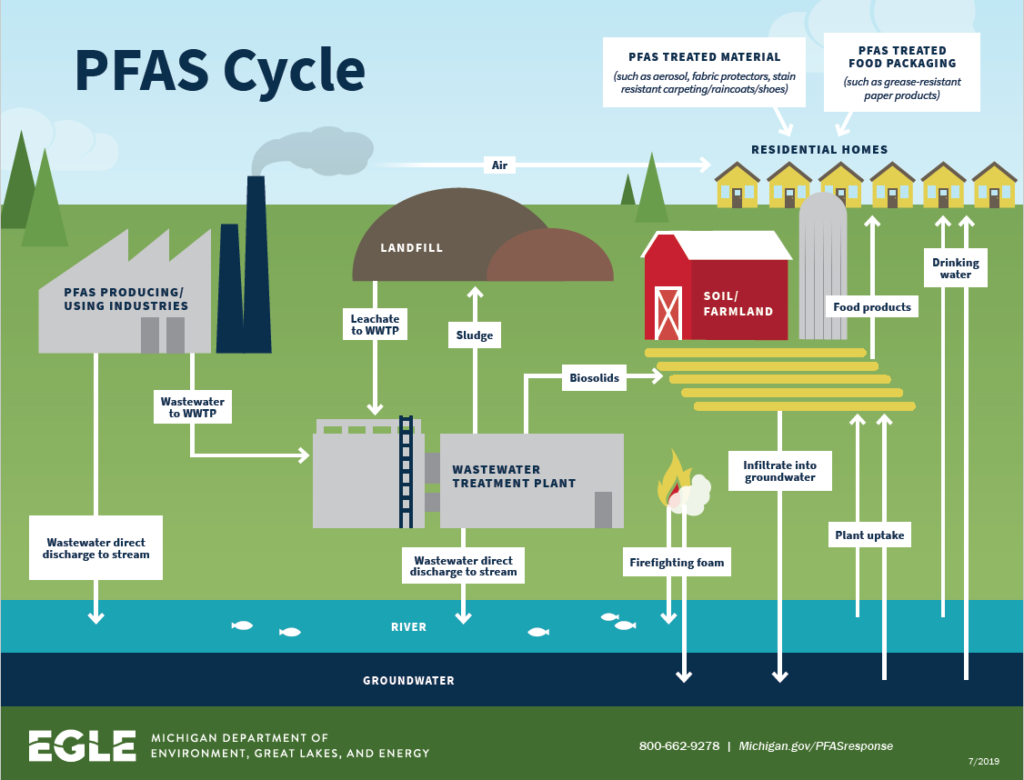

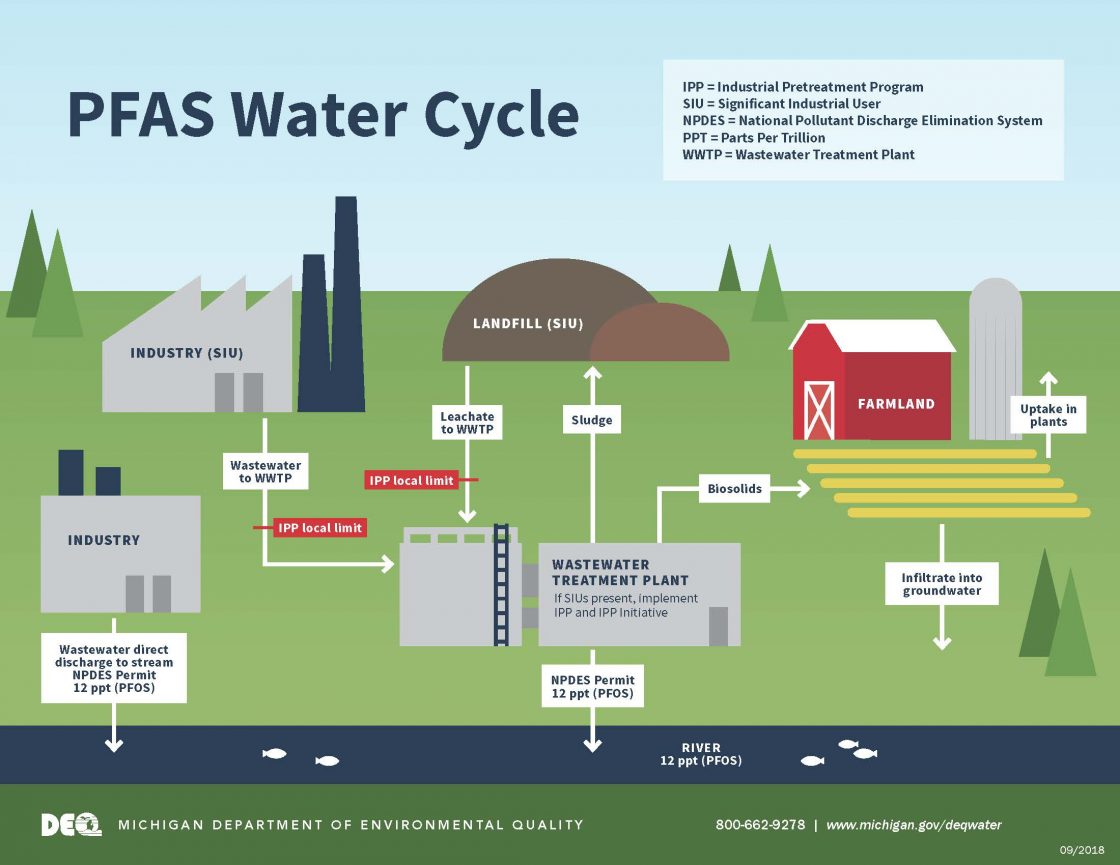

PFAS are manufactured compounds that are characterized by their strong carbon-fluorine bonds, making them resistant to heat, water, and oil. (So right off the bat we know that we don’t want these anywhere near our water supply.) While these properties have led to widespread use in manufacturing, they have also led to contamination in our water supplies thanks to industrial discharges, firefighting activities, and the destruction of consumer products.

Despite being in use for the past eight decades, these synthetic toxins are still categorized as emerging contaminants. For context, emerging contaminants are grouped into eight main categories: pharmaceuticals, PCPs, hormones and steroids, disinfectants, flame retardants, herbicides and pesticides, industrial additives, and gasoline additives.

This classification represents the lack of necessary regulatory limits for how much of these compounds can legally be in public drinking water. Since it is virtually impossible to destroy them (and it can be even harder to completely avoid them), the possibility of producing adverse side effects over time is high, with the potential to cause severe complications in both the environment and within the human body.

So, where can PFAS most commonly be found today?

- Soil, water, and/or PFAS-containing equipment and materials from PFAS-grown agricultural products.

- Drinking polluted groundwater from stormwater runoff near landfills, wastewater treatment plants, and firefighter training facilities.

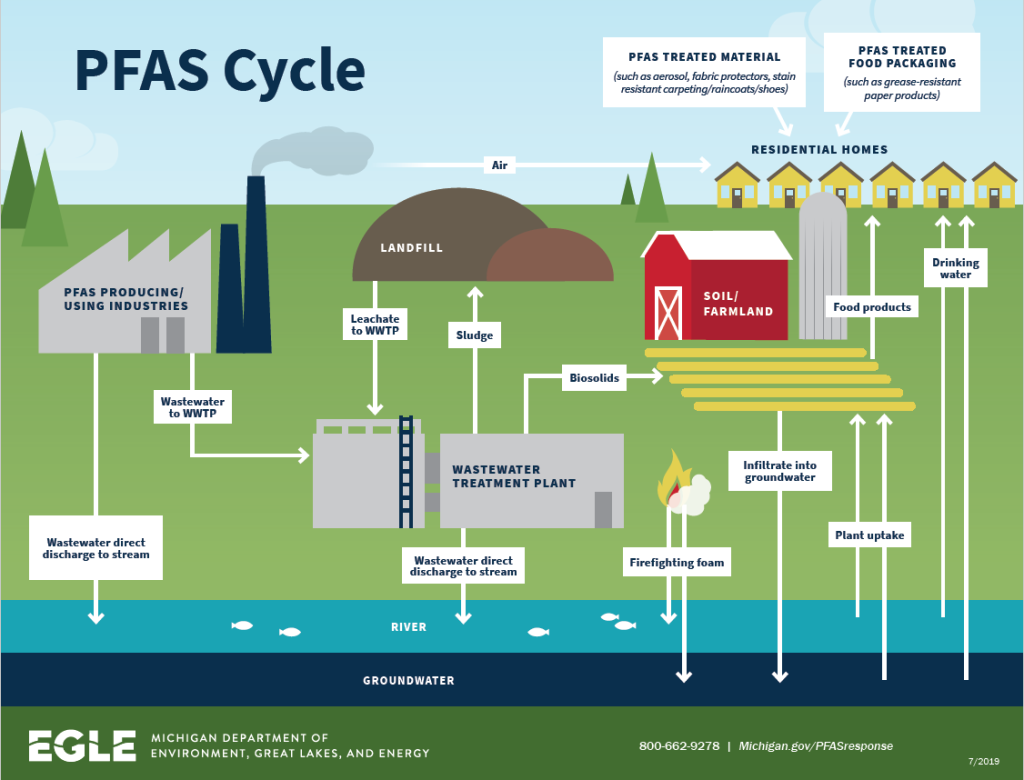

- Household items such as nonstick products (e.g., Teflon), polishes, waxes, paints, cleaning agents, and fabrics with stain and water repellency.

- Firefighting foams expelled at airports and military bases during firefighting exercises.

- Industrial facilities that utilize PFAS when manufacturing chrome plating, electronics, and oil recovery.

Mitigation Efforts

The role water utilities play in mitigating PFAS contamination simply cannot be overstated. In order to protect the community from contamination, utilities require a robust toolbelt: a combination of advanced technologies, vigorous monitoring and reporting systems, and extensive regulatory frameworks.

There’s also the option for more advanced treatment technologies, like activated carbon filtration and ion exchange, that can be used when trying to eliminate these toxic, persistent substances. Activated carbon filtration is when water passes through a bed of activated carbon particles that aid in absorbing PFAS contaminants. Ion exchange is another similar method that instead replaces the PFAS ions with less harmful ones, helping to reduce contamination levels.

Utilities take it one step further by conducting routine monitoring and testing at the sources, as it is crucial to being able to identify contamination early on and act fast. Combined with ongoing research, utilities are able to keep themselves on top of their mitigation practices and existing technologies.

Funding Difficulties

Now, we know that water utilities receive very limited funding and are the ones left behind to clean up the mess (pun intended). While grants can be incredibly helpful, they’re not guaranteed and can be far and few between.

In the summer of 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) introduced new health advisories related to PFAS contamination in public drinking water. This act aligned with President Biden’s initiative to provide clean drinking water to the American people, alongside an initial $1 billion grant, which was part of a larger $5 billion initiative. The grant was extended nationwide and was designated for comprehensive water testing, technical support, contractor training, and other essential action items. In addition, President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law invests $9 billion over five years to help communities that are on the frontlines of PFAS and other contamination reduce levels in drinking water.

However, $1–9 billion simply won’t cut it.

The insufficient amount is hardly enough to supply testing on a national scale, a necessary feat in rectifying almost 100 years of damage from PFAS contamination. Water utilities are then forced in between a rock and a hard place, leaving them with limited funds and ill-equipped to fix the contaminated waterways. The responsibility, unfortunately, falls onto utilities, when in reality, it should fall on the corporations that originally introduced PFAS, given the years of profiting from these compounds.

We’ve entered a time where it is now up to these corporations to contribute to the cleanup of our land and water, especially considering that public water systems are often the ones burdened with the financial repercussions.

Role of Manufacturers

Manufacturers, who have historically utilized PFAS in their products, play a significant role in addressing the contamination crisis. Even while advancements in alternative chemicals are currently underway, the responsibility to rectify the issue should really fall on to those who have played a hand in its creation. (Essentially, you break it, you buy it!)

As we know, the costs of detecting, treating, and preventing PFAS contamination place a hefty burden on water utilities. Manufacturers can help alleviate this financial strain. And besides, if manufacturers can express transparent acknowledgment of their past actions and make a full commitment to not only rectifying their wrongdoings but fronting the bills, it would build trust among the consumers and communities affected, making it some sort of a win-win.

Conclusion

In the face of PFAS contamination, knowledge is indeed power. Water utilities are armed with an understanding of the issue and have accepted their mission as the bodyguards of public health.

However, the challenges they face, including a lack of proper funding and the need for cooperation from manufacturers, often put a spotlight on the complexity of the issue. It is crucial for us as a society to recognize the shared responsibility in addressing PFAS contamination, making the intentional effort towards collaboration between stakeholders to make sure the burden does not disproportionately fall on those working diligently to provide safe and clean water to communities.

Through collective efforts and informed decision-making, we can pave the way for a sustainable and PFAS-free future.

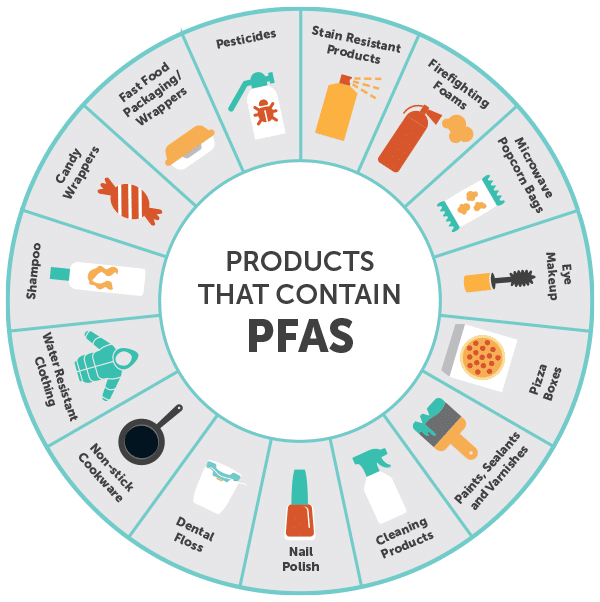

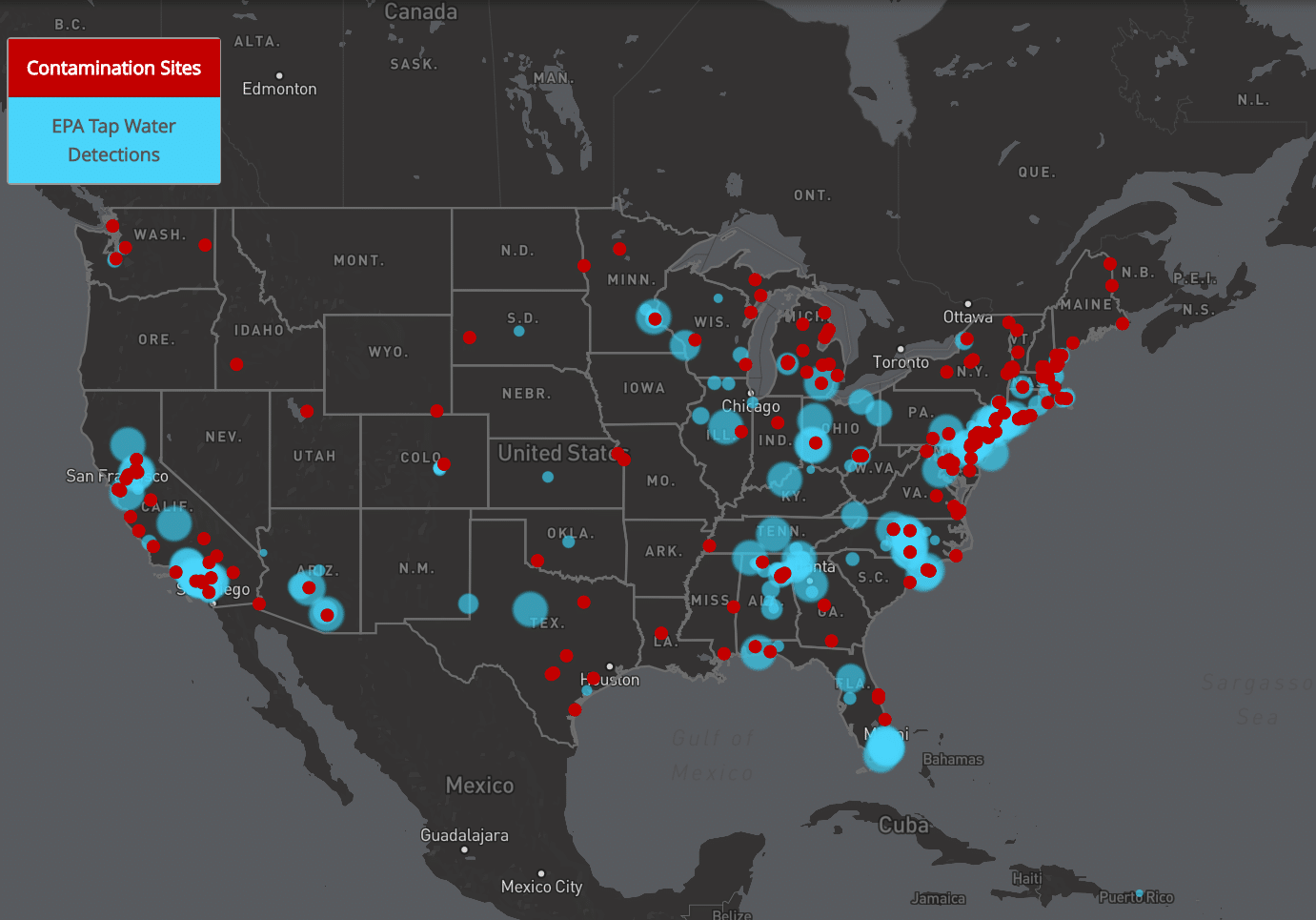

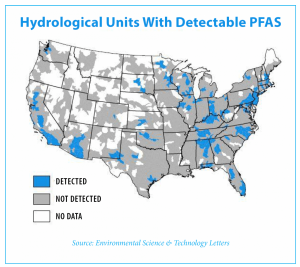

PFAS have been on the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) radar for quite some time now. The question is, why is the EPA so focused on these compounds? Well, for starters, they are human-made, widely used, and nearly impossible to dissolve and break down, which means that over time they start to spread and grow, more and more, both within the human body and in our environment. These compounds are also resistant to heat, oil, grease, and water, and —what’s worse — is that the EPA has found traces of all the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule 3 (UCMR 3) (i.e., the long p-words mentioned earlier) in our country’s water supply in recent years.

PFAS have been on the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) radar for quite some time now. The question is, why is the EPA so focused on these compounds? Well, for starters, they are human-made, widely used, and nearly impossible to dissolve and break down, which means that over time they start to spread and grow, more and more, both within the human body and in our environment. These compounds are also resistant to heat, oil, grease, and water, and —what’s worse — is that the EPA has found traces of all the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule 3 (UCMR 3) (i.e., the long p-words mentioned earlier) in our country’s water supply in recent years. Today,

Today,  At the end of the day, our planet’s drinking water has been affected on a national and global level thanks to the work of PFAS manufacturers. People, animals, and our entire ecosystem have been tainted. Now, water utilities are tasked with cleaning up the mess (literally). Grants are helpful but they’re not guaranteed and, frankly, $1-5 billion isn’t nearly enough for testing on a national scale, which is necessary due to the almost 100 years of damage PFAS have caused.

At the end of the day, our planet’s drinking water has been affected on a national and global level thanks to the work of PFAS manufacturers. People, animals, and our entire ecosystem have been tainted. Now, water utilities are tasked with cleaning up the mess (literally). Grants are helpful but they’re not guaranteed and, frankly, $1-5 billion isn’t nearly enough for testing on a national scale, which is necessary due to the almost 100 years of damage PFAS have caused.

According the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), all these UCMR 3 PFAS compounds have been detected in public water supplies across the US. Since PFAS are considered emerging contaminants, there are currently no established regulatory limits for levels in drinking water. However, in 2016, the EPA set Health Advisory levels (HA) of 0.07 micrograms per liter (µg/L) or 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for the combined concentrations of two PFAS compounds, PFOS and PFOA.

According the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), all these UCMR 3 PFAS compounds have been detected in public water supplies across the US. Since PFAS are considered emerging contaminants, there are currently no established regulatory limits for levels in drinking water. However, in 2016, the EPA set Health Advisory levels (HA) of 0.07 micrograms per liter (µg/L) or 70 parts per trillion (ppt) for the combined concentrations of two PFAS compounds, PFOS and PFOA. The EPA also recommends that treatment be implemented for all five PFAS when one or more of these compounds are present.

The EPA also recommends that treatment be implemented for all five PFAS when one or more of these compounds are present. Most research on the effects of PFAS on human health is based on animal studies. And, although there is no conclusive evidence that PFAS cause cancer, animal studies have shown there are possible links. However, PFAS ill-health effects are associated with changes in thyroid, kidney and liver function, as well as affects to the immune system. These chemicals have also caused fetal development effects during pregnancy and low birth weights.

Most research on the effects of PFAS on human health is based on animal studies. And, although there is no conclusive evidence that PFAS cause cancer, animal studies have shown there are possible links. However, PFAS ill-health effects are associated with changes in thyroid, kidney and liver function, as well as affects to the immune system. These chemicals have also caused fetal development effects during pregnancy and low birth weights.