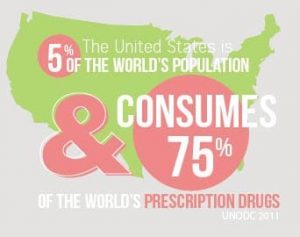

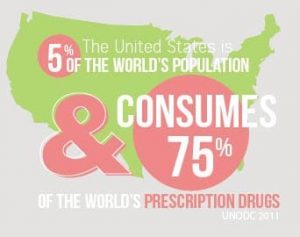

Modern-day, developed nations use an exorbitant amount of chemicals for a variety of reasons. Some of these chemicals are used to prevent and treat illness, to reduce pain from injury or surgery, to treat mental health issues, and for hygiene, grooming, and cosmetic reasons. Commonly referred to as Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, or PPCPs, these products include prescription and over-the-counter medications, cosmetics, fragrances, face and body washes, sunscreens, insect repellants, and lotions.

Modern-day, developed nations use an exorbitant amount of chemicals for a variety of reasons. Some of these chemicals are used to prevent and treat illness, to reduce pain from injury or surgery, to treat mental health issues, and for hygiene, grooming, and cosmetic reasons. Commonly referred to as Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, or PPCPs, these products include prescription and over-the-counter medications, cosmetics, fragrances, face and body washes, sunscreens, insect repellants, and lotions.

In addition to PPCPs are endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs). The endocrine system is an intricate network of glands including the thyroid, pituitary, adrenal, pancreas, thymus, and reproductive organs that release precise amounts of hormones into the bloodstream in order to regulate essential biological functions in humans and animals such as growth, development, reproduction, and metabolism. EDCs are any external natural or synthetic compounds capable of interfering with the body’s endocrine system by disrupting the synthesis, secretion, transport, bonding, or elimination of natural bodily hormones.

Effects of PPCPs and EDCs in Water

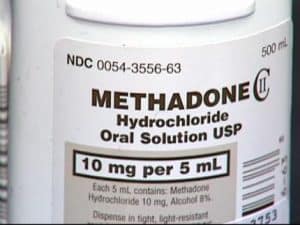

PPCPs and EDCs enter our waterways through sewage, leachate from landfills and septic systems, flushing of unused medications, and agricultural runoff, and they have the potential to cause a myriad of problems. While there has not yet been a truly significant amount of research completed on all of these products and chemicals, some facts are known. For example, excessive antibiotic use has led to the development of “superbugs,” or bacteria such as MRSA that are resistant to most antibiotics. Methadone reacts with chloramine, a chemical used to treat drinking water, to form N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a known carcinogen. EDCs interfere with the endocrine system, potentially causing reproductive, developmental, neurological, and immunologic problems in both humans and wildlife.

PPCPs and EDCs enter our waterways through sewage, leachate from landfills and septic systems, flushing of unused medications, and agricultural runoff, and they have the potential to cause a myriad of problems. While there has not yet been a truly significant amount of research completed on all of these products and chemicals, some facts are known. For example, excessive antibiotic use has led to the development of “superbugs,” or bacteria such as MRSA that are resistant to most antibiotics. Methadone reacts with chloramine, a chemical used to treat drinking water, to form N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), a known carcinogen. EDCs interfere with the endocrine system, potentially causing reproductive, developmental, neurological, and immunologic problems in both humans and wildlife.

Some of the most common EDCs in drinking water include estrogen and progesterone from birth control pills, as well as anabolic steroids. These compounds interfere with the reproductive capabilities of aquatic wildlife. Examples include eggshell thinning and subsequent reproductive failure of waterfowl; reduced populations of Baltic seals due to lower fertility and increased miscarriage; development of male reproductive organs in female marine animals, such as snails; feminization and subsequent decreased populations of certain types of fish, including bass; and reduced or malformed frog populations.

Some of the most common EDCs in drinking water include estrogen and progesterone from birth control pills, as well as anabolic steroids. These compounds interfere with the reproductive capabilities of aquatic wildlife. Examples include eggshell thinning and subsequent reproductive failure of waterfowl; reduced populations of Baltic seals due to lower fertility and increased miscarriage; development of male reproductive organs in female marine animals, such as snails; feminization and subsequent decreased populations of certain types of fish, including bass; and reduced or malformed frog populations.

Regulating PPCPs and EDCs in Drinking Water

Currently, most PPCPs and EDCs are not regulated at either the state or federal level; however, they are being investigated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as Contaminants of Emerging Concern. Because PPCPs and EDCs appear to hinder reproduction in marine life, many state environmental organizations strongly support additional research and potential regulation on these compounds. In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to set drinking water and cleanup standards for the known EDC perchlorate after it had been detected in the state’s drinking water, and many states have implemented public education campaigns on these compounds, their effects, and their proper disposal.

Currently, most PPCPs and EDCs are not regulated at either the state or federal level; however, they are being investigated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as Contaminants of Emerging Concern. Because PPCPs and EDCs appear to hinder reproduction in marine life, many state environmental organizations strongly support additional research and potential regulation on these compounds. In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to set drinking water and cleanup standards for the known EDC perchlorate after it had been detected in the state’s drinking water, and many states have implemented public education campaigns on these compounds, their effects, and their proper disposal.

Treating PPCPs and EDCs in Drinking Water

Currently, there are no treatment processes specifically designed to remove PPCPs or EDCs from drinking water; however, research is currently underway at the national level to determine the effectiveness of existing drinking water treatment technologies, such as chlorination, carbon filtration, and ozonation, on the removal of PPCPs and EDCs. In addition, several new, innovative technologies that specifically target PPCPs and EDCs for removal have shown promise. One example utilizes a catalyst called TAML(r), which is iron plus tetra-amido macrocyclic ligand, to remove PPCPs and EDCs from wastewater, while another utilizes zeolite adsorption to remove PPCPs and EDCs from water.

How We All Can Help Reduce PPCPs and EDCs in the Environment

On an individual level, taking small, simple steps can have a large impact on the amount of PPCPs and EDCs in our water supply:

On an individual level, taking small, simple steps can have a large impact on the amount of PPCPs and EDCs in our water supply:

- Ask your health care provider to prescribe no more than the sufficient, effective quantity of medication, or consider a trial prescription before filling the full 30- to 90-day supply;

- Buy OTC medications in small enough quantities that can be used before the expiration date;

- Return all unused medications to pharmaceutical take-back programs that allow the public to bring unused drugs to a central location for proper disposal;

- If a community take-back location is unavailable, remove unused or expired prescription medications from their original containers and throw them in the trash – never flush! To discourage abuse of certain types of dangerous medications such as narcotics, crush the pills and mix them with old bacon grease or other food waste.

In Conclusion

The problem of PPCPs and EDCs in drinking water does not appear to be going away any time soon. In order to mitigate damage caused to both humanity and the environment, additional research and focus must be placed on these compounds. It is imperative that we implement additional regulations, engineer innovative and cost-effective treatment technologies, increase funding to upgrade infrastructure, and reduce our personal contributions of PPCPs and EDCs to the environment.

Modern-day, developed nations use an exorbitant amount of chemicals for a variety of reasons. Some of these chemicals are used to prevent and treat illness, to reduce pain from injury or surgery, to treat mental health issues, and for hygiene, grooming, and cosmetic reasons. Commonly referred to as Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, or PPCPs, these products include prescription and over-the-counter medications, cosmetics, fragrances, face and body washes, sunscreens, insect repellants, and lotions.

Modern-day, developed nations use an exorbitant amount of chemicals for a variety of reasons. Some of these chemicals are used to prevent and treat illness, to reduce pain from injury or surgery, to treat mental health issues, and for hygiene, grooming, and cosmetic reasons. Commonly referred to as Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products, or PPCPs, these products include prescription and over-the-counter medications, cosmetics, fragrances, face and body washes, sunscreens, insect repellants, and lotions. PPCPs and EDCs enter our waterways through sewage, leachate from landfills and septic systems, flushing of unused medications, and agricultural runoff, and they have the potential to cause a myriad of problems. While there has not yet been a truly significant amount of research completed on all of these products and chemicals, some facts are known. For example, excessive antibiotic use has led to the development of “superbugs,” or bacteria such as MRSA that are resistant to most antibiotics.

PPCPs and EDCs enter our waterways through sewage, leachate from landfills and septic systems, flushing of unused medications, and agricultural runoff, and they have the potential to cause a myriad of problems. While there has not yet been a truly significant amount of research completed on all of these products and chemicals, some facts are known. For example, excessive antibiotic use has led to the development of “superbugs,” or bacteria such as MRSA that are resistant to most antibiotics.  Some of the most common EDCs in drinking water include estrogen and progesterone from birth control pills, as well as anabolic steroids. These compounds interfere with the reproductive capabilities of aquatic wildlife. Examples include eggshell thinning and subsequent reproductive failure of waterfowl; reduced populations of Baltic seals due to lower fertility and increased miscarriage; development of male reproductive organs in female marine animals, such as snails; feminization and subsequent decreased populations of certain types of fish, including bass; and reduced or malformed frog populations.

Some of the most common EDCs in drinking water include estrogen and progesterone from birth control pills, as well as anabolic steroids. These compounds interfere with the reproductive capabilities of aquatic wildlife. Examples include eggshell thinning and subsequent reproductive failure of waterfowl; reduced populations of Baltic seals due to lower fertility and increased miscarriage; development of male reproductive organs in female marine animals, such as snails; feminization and subsequent decreased populations of certain types of fish, including bass; and reduced or malformed frog populations. Currently, most PPCPs and EDCs are not regulated at either the state or federal level; however, they are being investigated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as Contaminants of Emerging Concern. Because PPCPs and EDCs appear to hinder reproduction in marine life, many state environmental organizations strongly support additional research and potential regulation on these compounds. In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to set drinking water and cleanup standards for the known EDC perchlorate after it had been detected in the state’s drinking water, and many states have implemented public education campaigns on these compounds, their effects, and their proper disposal.

Currently, most PPCPs and EDCs are not regulated at either the state or federal level; however, they are being investigated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as Contaminants of Emerging Concern. Because PPCPs and EDCs appear to hinder reproduction in marine life, many state environmental organizations strongly support additional research and potential regulation on these compounds. In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state in the nation to set drinking water and cleanup standards for the known EDC perchlorate after it had been detected in the state’s drinking water, and many states have implemented public education campaigns on these compounds, their effects, and their proper disposal. On an individual level, taking small, simple steps can have a large impact on the amount of PPCPs and EDCs in our water supply:

On an individual level, taking small, simple steps can have a large impact on the amount of PPCPs and EDCs in our water supply: