Water systems today face a set of problems that are unique to this generation. While our nation’s buried infrastructure is crumbling beneath our feet as it reaches the end of its useful life, supplies are dwindling, budgets are shrinking, and federal and state funding is drying up. At the same time, regulatory requirements continue to increase as emerging contaminants are identified. Water systems often find themselves in the quandary of whether to upgrade treatment systems to comply with these new regulations or update assets that are long overdue for replacement or rehabilitation.

Water systems today face a set of problems that are unique to this generation. While our nation’s buried infrastructure is crumbling beneath our feet as it reaches the end of its useful life, supplies are dwindling, budgets are shrinking, and federal and state funding is drying up. At the same time, regulatory requirements continue to increase as emerging contaminants are identified. Water systems often find themselves in the quandary of whether to upgrade treatment systems to comply with these new regulations or update assets that are long overdue for replacement or rehabilitation.

Savvy DPW directors recognize the need for thinking outside the box when it comes to water system management. Gone are the days of simply allocating annual budgets to the required maintenance of assets. Instead, careful planning, thoughtful operations, and superior efficiency are the new requirements for successful utility management, and can all be accomplished with limited capital investment.

Planning for the Future with Capital Efficiency Plans™

Asset management planning is critical to the health and maintenance of water utilities. Part of a successful asset management plan is the development of a planned, systematic approach that provides for the rehabilitation and replacement of assets over time, while also maintaining an acceptable level of service for existing assets. But how are utilities able to determine which assets should be prioritized? The answer is through a multi-faceted approach to asset management.

Our Capital Efficiency Plan™ (CEP) methodology is unique in that it combines the concepts of asset management, hydraulic modeling, and system criticality into a single comprehensive report that is entirely customized to the individual utility distribution system. The final report provides utilities with a database and Geographic Information System (GIS) representation for each pipe segment within their underground piping system, prioritizes water distribution system piping improvements, and provides estimated costs for water main replacement and rehabilitation. Because the CEP takes a highly structured, three-pronged approach, utilities can decisively prioritize those assets most in need of repair or replacement, and are able to justify the costs of those critical projects when preparing annual budgets.

Increasing Operational Efficiency with Business Practice Evaluations

In addition to addressing capital efficiency, water utilities of today must also address operational efficiency. Because water systems are required to do so much with so little, efficiency in all aspects of water system management is critical. Tata & Howard appreciates the unique set of challenges faced by water systems today, and we have experts on staff who understand the inner workings of a water utility – and how to improve them.

In addition to addressing capital efficiency, water utilities of today must also address operational efficiency. Because water systems are required to do so much with so little, efficiency in all aspects of water system management is critical. Tata & Howard appreciates the unique set of challenges faced by water systems today, and we have experts on staff who understand the inner workings of a water utility – and how to improve them.

Our Business Practice Evaluation (BPE) was designed by James J. “Jim” Courchaine, Vice President and National Director of Business Practices, who has over 45 years of experience in every facet of water and wastewater management, operations, and maintenance. He is a certified Water Treatment and Distribution System Operator, Grade 4c (MA) and RAM-W (Risk Assessment Methodology for Water). He also taught courses at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell for ten years on water system operations. Jim does not approach utility operations from the perspective of an engineer; rather, he has deep experience in utility operations and management as an actual operator.

Our BPEs assess the health of a utility’s work practices by implementing a framework for a structured approach to managing, operating, and maintaining in a well-defined manner. The overall goal of the assessment process is more efficient and effective work practices, and the assessment includes documentation of current business practices, identification of opportunities for improvement, conducting interviews including a diagonal slice of the organization, and observation of work practices in the field. The BPE encourages utilities to operate as a for-profit business rather than as a public supplier, which results in more efficient, cost effective operational and managerial procedures — and an improved bottom line. Water systems that have conducted a BPE have found significant improvement in the operational efficiency of their utility.

Improving the Environment — and the Bottom Line — with Water Audits

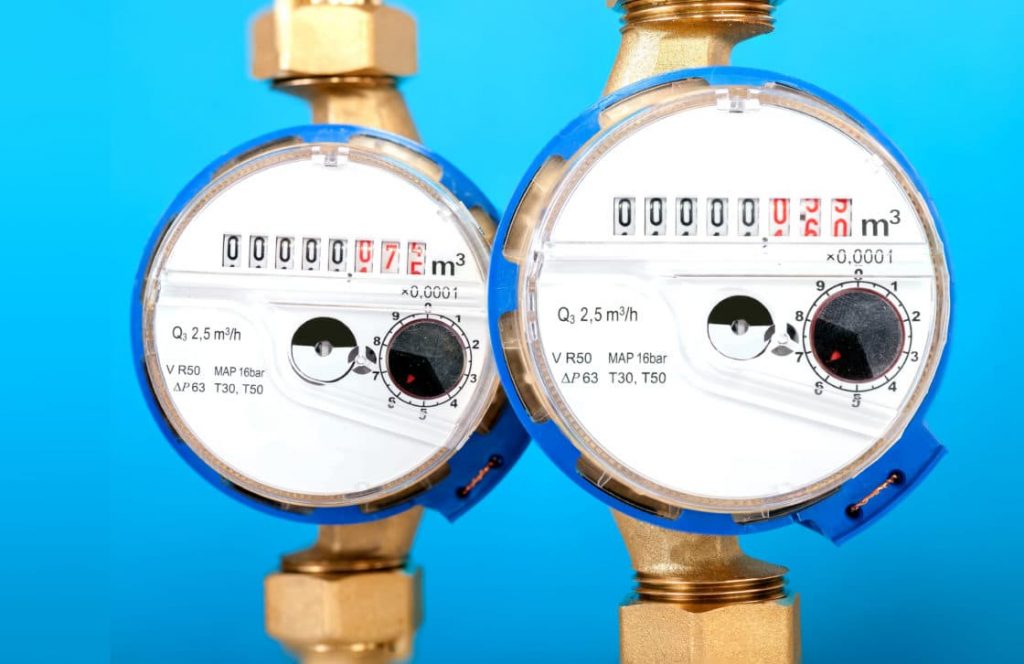

Besides improving operational and capital efficiency, water systems of today must reduce non-revenue water. Non-revenue water is treated drinking water that has been pumped but is lost before it ever reaches the customer, either through real losses such as leaks, or through apparent losses such as theft or metering issues. In the United States, water utilities lose about 20% of their supply to non-revenue water. Non-revenue water not only affects the financial health of water systems, but also contributes to our nation’s decreasing water supply. In fact, the amount of water “lost” over the course of a year is enough to supply the entire State of California for that same year. Therefore, the AWWA recommends that every water system conduct an annual water audit using M36: Water Audits and Loss Control methodology to accurately account for real and apparent losses.

Besides improving operational and capital efficiency, water systems of today must reduce non-revenue water. Non-revenue water is treated drinking water that has been pumped but is lost before it ever reaches the customer, either through real losses such as leaks, or through apparent losses such as theft or metering issues. In the United States, water utilities lose about 20% of their supply to non-revenue water. Non-revenue water not only affects the financial health of water systems, but also contributes to our nation’s decreasing water supply. In fact, the amount of water “lost” over the course of a year is enough to supply the entire State of California for that same year. Therefore, the AWWA recommends that every water system conduct an annual water audit using M36: Water Audits and Loss Control methodology to accurately account for real and apparent losses.

A water audit helps water systems identify the causes of water loss, as well as the true costs of this loss. An effective water audit will help a water system reduce water loss, thus recapturing lost revenue. Water loss typically comes as a result of aging, and deteriorating infrastructure, particularly in the northeast, as well as policies and procedures that lead to inaccurate accounting of water use. Water audits are the most cost-effective and efficient solution to increasing demand, and, like BPEs, water audits usually pay for themselves in less than a year.

In Conclusion

Today’s DPW Directors are faced with the burden of increasing regulations along with decreasing supply, budgets, and funding. For water systems to continue to effectively function, they must remain profitable, which means they must implement efficiencies on all fronts. CEPs, BPEs, and water audits are all low-cost methodologies that improve efficiency with an extremely short return on investment. In addition, water systems that proactively plan for the future will more easily weather the threats of climate change and population growth. Capital and operational efficiency combined with identifying and addressing sources of non-revenue water will position water system to continue to provide safe, clean drinking water for future generations.

It is widely known how important water is to our lives and the world we live in. Our body and planet is comprised of about 70% water – making it seem like it is easily accessible and plentiful. However, when you rule out our oceans and ice caps, less than 1% of all the water on Earth is drinkable. Of that less than 1%, groundwater only accounts for 0.28% of fresh water around the globe. Safe drinking water is a privilege we often take for granted while we brush our teeth or drink a glass of water in the morning. While we are giving thanks to our family, friends, and food during Thanksgiving, we should also give big thanks for our clean drinking water and the people who make it happen.

It is widely known how important water is to our lives and the world we live in. Our body and planet is comprised of about 70% water – making it seem like it is easily accessible and plentiful. However, when you rule out our oceans and ice caps, less than 1% of all the water on Earth is drinkable. Of that less than 1%, groundwater only accounts for 0.28% of fresh water around the globe. Safe drinking water is a privilege we often take for granted while we brush our teeth or drink a glass of water in the morning. While we are giving thanks to our family, friends, and food during Thanksgiving, we should also give big thanks for our clean drinking water and the people who make it happen.

October 23-29 is National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2016. Established in 1999 by the U.S. Senate, National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week (NLPPW) occurs every year during the last week in October and is now supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the World Health Organization (WHO). This year’s NLPPW theme of “Lead-Free Kids for a Healthy Future” underscores the importance of protecting our future by educating the public about the dangers and sources of lead poisoning and what can be done to prevent it. While lead-based paint is arguably the most common and hazardous source of lead exposure for young children,

October 23-29 is National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2016. Established in 1999 by the U.S. Senate, National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week (NLPPW) occurs every year during the last week in October and is now supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the World Health Organization (WHO). This year’s NLPPW theme of “Lead-Free Kids for a Healthy Future” underscores the importance of protecting our future by educating the public about the dangers and sources of lead poisoning and what can be done to prevent it. While lead-based paint is arguably the most common and hazardous source of lead exposure for young children,

Lead in drinking water cannot be detected through taste or smell, and the only way to know for certain if your drinking water has elevated lead levels is to have your water professionally tested. Typically, lead pipes are found in homes that were built prior to 1986 and in older cities. Older homes with private wells are also at risk of having lead in drinking water. While

Lead in drinking water cannot be detected through taste or smell, and the only way to know for certain if your drinking water has elevated lead levels is to have your water professionally tested. Typically, lead pipes are found in homes that were built prior to 1986 and in older cities. Older homes with private wells are also at risk of having lead in drinking water. While